the famous "Catwalk Site", one of the open air displays at the National Museums of Kenya Olorgesailie site museum, which is littered with ~900,000 year old handaxes. Photo courtesy

of Briana Pobiner.

|

Top 6 Human Evolution Discoveries of 2018

11 December 2018

Here we are, once again, at the end of a calendar year filled with lots of exciting news in the field of human evolution. Last year, just as we were finalizing edits on the 2017 Top 5 Human Evolution Discoveries list, the remainder of the skeleton of a human ancestor known colloquially as "Little Foot" (belonging to the genus Australopithecus, the same genus, but different species, as the famed "Lucy" fossil) was finally revealed after 20 years of cleaning and excavation from its embedding rock. Amazingly, just as we are finishing the edits for this year's installment of top human evolution discoveries, Little Foot is back in the news. As of the last week of November, full descriptions and analyses of the remainder of the fossils are now available (prior to undergoing peer-review) on the preprint server bioRxiv. Enjoy reading our Top 6 list for 2018! Why 6? These stories are too cool not to share. - JMO

By Ella Beaudoin, BA, and Briana Pobiner, PhD, Human Origins Program, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History

What does it mean to be human? What makes us unique among all other organisms on Earth? Is it cooperation? Conflict? Creativity? Cognition? There happens to be one anatomical feature that distinguishes modern humans (Homo sapiens) from every other living and extinct animal: our bony chin! But does a feature of our jaws have actual meaning for our humanity? We want to talk about the top six discoveries of 2018, all from the last 500,000 years of human evolution, that give us more insight into what it means to be human. If you want to learn more about our favorite discoveries from last year, read our 2017 blog post!

1) Migrating modern humans: the oldest modern human fossil found outside of Africa

Every person alive on the planet today is a Homo sapiens,and our species evolved around 300,000 years ago in Africa. In January of this year, a team of archaeologists led by Israel Hershkovitz from Tel Aviv University in Israel made a stunning discovery at a site on the western slope of Mount Carmel in Israel - Misliya Cave. This site had previously yielded flint artifacts dated to between 140,000 and 250,000 years ago, and the assumption was that these tools were made by Neanderthals which had also occupied Israel at this time. But tucked in the same layer of sediment as the stone tools was a Homo sapiens upper jaw! Dated to between 177,000 and 194,000 years ago by three different dating techniques, this finding pushes back the evidence for human expansion out of Africa by roughly 40,000 years. It also supports the idea that there were multiple waves of modern humans migrating out of Africa during this time, some of which may not have survived to pass on their genes to modern humans alive today. Remarkably, this jawbone was discovered by a freshman student at Tel Aviv University working on his first archaeological dig in 2002! So, there is hope for students wishing to make a splash in this field!

2) Innovating modern humans: long-distance trade, the use of color, and the oldest Middle Stone Age tools in Africa

At the prehistoric site of Olorgesailie in southern Kenya, years of careful climate research and meticulous excavation by a research team lead by Rick Potts of the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History and Alison Brooks of George Washington University were able to explore both the archaeological and paleoenvironmental records to document behavioral change by modern humans in response to climatic variation. The artifacts show a shift from the larger and clunkier tools of the Acheulean, characterized by teardrop-shaped handaxes, to the more sophisticated and specialized tools of the Middle Stone Age (MSA). The MSA tools were dated to 320,000 years ago, the earliest evidence of this kind of technology in Africa. They also found evidence that one of the kinds of rock used to make the MSA tools, obsidian, was obtained from at least 55 miles (95 kilometers) away. Such long distances led the teams to conclude that obsidian was traded in social networks, since this is much further than modern human forager groups typically travel in a day. On top of that, the team found red and black rocks (pigments) used for coloring material in the MSA sites, indicating symbolic communication, possibly used to maintain these social networks with distant groups. Finally, all of these innovations occurred during a time of great climate and landscape instability and unpredictability, with a major change in mammal species (about 85%). In the face of this uncertainty, early members of our species seem to have responded by developing technological innovations, greater social connections, and symbolic communication. These exciting findings were published in a set of three papers in Science, focused on the dating of these finds; the stone tool technology and transport and use of pigments; and the earlier changes in environments and technology that anticipate later characteristics of the stone tools.

(Featured image at the top of this post is the famous "Catwalk Site", one of the open air displays at the National Museums of Kenya Olorgesailie site museum, which is littered with ~900,000 year old handaxes. Photo courtesy of Briana Pobiner.)

3) Art-making Neanderthals: our close evolutionary cousins actually created the oldest known cave paintings

Neanderthals are often imagined as primitive brutes dragging clubs behind them. But new discoveries, including one made last year, continue to reshape that image. A team led by Alistair Pike from the University of Southampton found red ocher paintings - dots, boxes, abstract animal figures, and handprints - deep inside three Spanish caves. The most amazing part? These paintings dated to at least 65,000 years ago–a full 20,000-25,000 years before Homo sapiens arrived in Europe (which was 40,000 to 45,000 years ago)! The age of the paintings was determined by using uranium-thorium dating of white crusts made of calcium carbonate that had formed on top of the paintings by water percolating through the rocks. Since the calcite precipitated on top of the paintings, the paintings must have been there first - so they are older than the age of the calcite. The age of the paintings suggests that Neanderthals made them. It has been generally assumed that symbolic thought (the representation of reality through abstract concepts, such as art) was a uniquely Homo sapiensability. But sharing our ability for symbolic thought with Neanderthals means we may have to redraw our images of Neanderthal in popular culture: forget the club, maybe they should be holding paint brushes instead.

4) Trekking modern humans: the oldest modern human footprints in North America

When we think about how we make our marks on this world, we often picture leaving behind cave paintings, structures, old fire pits, and discarded objects. But even a footprint can leave behind traces of past movement! A discovery this year by a team led by Duncan McLaran from the University of Victoria with representatives from the Heiltsuk and Wuikinuxv First Nations revealed the oldest footprints in North America! These 29 footprints were made by at least three people on the tiny Canadian island of Calvert. The team used Carbon-14 dating of fossilized wood found in association with the footprints to date the find to 13,000 years ago. This site may have been a stop on a late Pleistocene coastal route humans used when migrating from Asia to the Americas. Because of their small size, some of the footprints must have been made by a child - who would have worn about a size 7 kids shoe today, if they were wearing shoes (interestingly, the evidence indicates they were walking barefoot). As humans, our social and caregiving nature has been essential to our survival. One of the research team members, Jennifer Walkus, mentioned why the child's footprints were particularly special: "Because so often kids are absent from the archeological record. This really makes the archaeology more personal." Any site with preserved human footprints is pretty special, as there are currently only a few dozen in the world.

5) Winter-stressed, nursing Neanderthals: Neanderthal children's teeth reveal intimate details of their daily lives

Evidence of children is very rare in the prehistoric archaeological record; their bones are more delicate than those of adults and therefore less likely to survive and fossilize, and their material artifacts are also almost impossible to identify. For instance, a stone tool made by a child might be interpreted as made hastily or by a novice, and toys are quite a new invention. To find remains that are conclusively juvenile is very exciting to archaeologists - not only for the personal connection we feel, but for the new insights we can learn about how individuals grew, flourished, and according to a new study led by Dr. Tanya Smith from Griffith University in Australia, suffered. Smith and her team studied the teeth of two Neanderthal children who lived 250,000 years ago in southern France. They took thin sections of the two teeth and "read" the layers of enamel, which develops in a way similar to tree rings: in times of stress, slight variations occur in the layers of tooth enamel. The tooth enamel chemistry also recorded environmental variation based on the climate where the Neanderthals grew up, because it reflects the chemistry of the water and the food that the Neanderthals kids ate and drank. The team determined that the two young Neanderthals were physically stressed during the winter months - they likely experienced fevers, vitamin deficiency, or disease more often during the colder seasons. The team found repeated high levels of lead exposure in both Neanderthal teeth, though the exact source of the lead is unclear - it could have been from eating or drinking contaminated food or water, or inhaling smoke from a fire made from contaminated material. They also found that one of the Neanderthals was born in the spring and weaned in the fall, and nursed until it was about 2.5 years old, similar to the average age of weaning in non-industrial modern human populations. (Our closest living relatives (chimpanzees and bonobos) nurse for much longer than we do, up to 5 years.) Discoveries like this are another indication that Neanderthals are more similar to Homo sapiensthan we had ever thought. Paleoanthropologist Kristin Krueger notes how discoveries like this are making "the dividing line between 'them' and 'us' [become more blurry] every day."

6) Hybridizing hominins: the first discovery of an ancient human hybrid

Speaking of blurring lines (and probably the biggest story of the year): a new discovery from Denisova Cave in Siberia has added to the complicated history of Neanderthals and other ancient human species. While Neanderthal fossils have been known for nearly two centuries, Denisovans are a population of hominins only discovered in 2008 based on the sequencing of their genome from a 41,000-year-old finger bone fragment from Denisova Cave - which was also inhabited by Neanderthals and modern humans (and whom they also mated with). While all of the known Denisovan fossils could nearly fit in one of your hands, the amount of information we can gain from their DNA is enormous! This year, a stunning discovery was made from a fragment of a long bone identified as coming from a 13-year-old girl nicknamed "Denny" who lived about 90,000 years ago: she was the daughter of a Neanderthal mother and Denisovan father. A team led by Viviane Slon and Svante Pääbo from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany first looked at her mitochondrial DNA and found that it was Neanderthal - but that didn't seem to be her whole genetic story. They then sequenced her nuclear genome and compared it to the genomes of other Neanderthals and Denisovans from the same cave, and compared it to a modern human with no Neanderthal ancestry. They found that about 40% of Denny's DNA fragments matched a Neanderthal genome, and another 40% matched a Denisovan genome. The team then realized that this meant she had acquired one set of chromosomes from each of her parents, who must have been two different types of early humans. Since her mitochondrial DNA - which is inherited from your mother - was Neanderthal, the team could say with certainty that her mother was a Neanderthal and a father that was Denisovan. However, the research team is very careful about not using the word "hybrid" in their paper, instead stating instead that Denny is a "first generation person of mixed ancestry." They note the tenuous nature of the biological species concept: the idea that one major way to distinguish one species from another is that individuals of different species cannot mate and produce fertile offspring. Yet we see interbreeding commonly occurring in the natural world, especially when two populations seem to be in the early stages of speciating - because speciation is a process that often takes a long time. It is clear from genetic evidence that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens individuals were sometimes able to mate and produce children, but it is unclear if these matings included difficulty with becoming pregnant or bringing a fetus to term - and modern human females and Neanderthal males may have had particular trouble making babies. While Neanderthals contributed DNA to the modern human genome, the reverse seems not to have occurred. Regardless of the complicated history of intermingling of different early human groups, Dr. Skoglund from the Francis Crick institute echoes what many other researchers are thinking about this amazing discovery, "[that Denny might be] the most fascinating person who has had their genome sequenced."

Source: https://blogs.plos.org/scicomm/2018/12/11/top-6-human-evolution-discoveries-of-2018/

|

(Isabel Cáceres/IPHES)

|

2.4-Million-Year-Old Tools Uncovered in North Africa

29 November 2018

BURGOS, SPAIN - Science News reports that stone tools unearthed in Algeria amid butchered animal bones suggest the evolution of human ancestors was not limited to East Africa. Mohamed Sahnouni of Spain's National Research Center for Human Evolution and his colleagues say meat-chopping tools found in North Africa were made about 2.4 million years ago, or about 200,000 years more recently than the oldest known tools in East Africa. The scientists think the tools could have been crafted by descendants of East African toolmakers who migrated into North Africa, or they may have been created independently. The animal bones came from savanna-dwellers such as elephants, horses, rhinoceroses, antelopes, and crocodiles that may have been hunted or scavenged from carnovores' fresh kill sites, Sahnouni said. No hominin remains were found with the tools, so the researchers are not sure who made them.

Source: https://www.archaeology.org/news/7172-181129-north-africa-hominins

|

(J. Tyler Faith)

|

New Thoughts on Africa's Megafauna Extinctions

26 November 2018

SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH - According to a Cosmos Magazine report, environmental changes are more likely to have wiped out Africa's megafauna than is hunting by Homo erectus, which emerged some 1.9 million years ago and has previously been blamed for causing the extinctions. Paleoecologist Tyler Faith of the University of Utah and his colleagues examined more than 100 fossil assemblages spanning the past seven million years found in Kenya, Tanzania, and Ethiopia. The researchers found that African megafauna species of elephants, hippos, rhinoceroses, giraffes, and camels began to decline some 4.6 million years ago, or about 2.5 million years before the arrival of H. erectus. Faith adds that the rate of extinction did not accelerate when H. erectus finally emerged. Analysis of climate data, changes in soil chemistry, and trace elements in animal teeth suggests that a global drop in levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide led to expansion of grasslands and loss of forests and woody vegetation that the large-bodied mammals relied upon for food. "It's really a long-term ecological process that's really difficult to pin on increased carnivory by the tool-using, meat-eating hominids," Faith said.

Source: https://www.archaeology.org/news/7163-181126-africa-megafauna-extinction

|

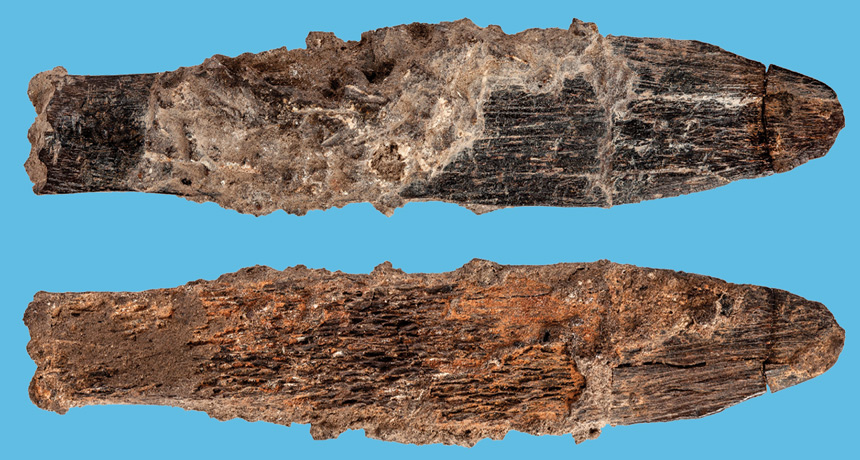

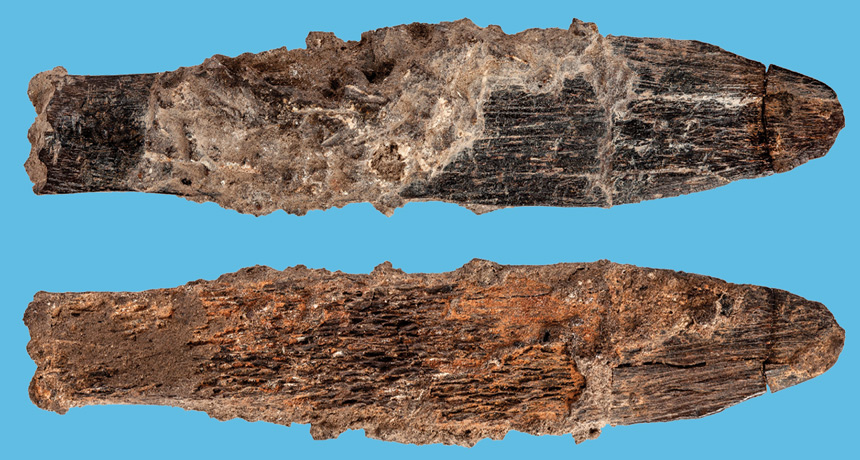

The discovery of a 90,000-year-old knife made of animal bone (shown here from both sides) in Morocco points to the ancient emergence of specialized toolmaking in northern Africa.

|

A 90,000-year-old bone knife hints special tools appeared early in Africa

3 October 2018

Africa's Stone Age was also a Bone Age.

Ancient Africans took bone tools to a new level around 90,000 years ago by making pointed knives out of animals' ribs, scientists say. Before then, bone tools served as simpler, general-purpose cutting devices.

Members of northern Africa's Aterian culture, which originated roughly 145,000 years ago, started crafting sharp-tipped bone knives as fish and other seafood increasingly became dietary staples, researchers suggest online October 3 in PLOS ONE. The new find supports the view that strategic planning for survival and associated changes in toolmaking emerged much earlier in human evolution than has traditionally been assumed.

Excavations inside Dar es-Soltan 1 cave, near Morocco's Atlantic coast, uncovered the bone knife in 2012, says a team led by geoarchaeologist Abdeljalil Bouzouggar of the National Institute of Archaeological and Heritage Sciences in Rabat, Morocco, and biological anthropologist Silvia Bello of the Natural History Museum in London. The knife's base and its broken-off tip were embedded in sediment that dates to about 90,000 years ago.

To make the knife, ancient humans first removed part of a cattle-sized animal's rib and cut it in half lengthwise. Toolmakers then scraped and chipped one of the halves into a nearly 13-centimeter-long knifelike shape.

Light damage to the find indicates that Aterians used the knife primarily to cut soft material, such as leather, Bello says. "Whatever its use, this tool was produced by very skilled manufacturers."

Two knife-shaped bone tools previously found at another Aterian site in Morocco lack precise age estimates, but are about as old as the Dar es-Soltan 1 discovery, the researchers estimate.

Specialized bone tools found more than 20 years ago in central Africa also date to 90,000 years ago (SN: 4/29/95, p. 260). Other parts of Africa witnessed shifts in stone-tool making and other behaviors by that time (SN: 10/13/18, p. 6).

Source: https://www.sciencenews.org/article/ancient-bone-knife-hints-special-tools-appeared-early-africa

|

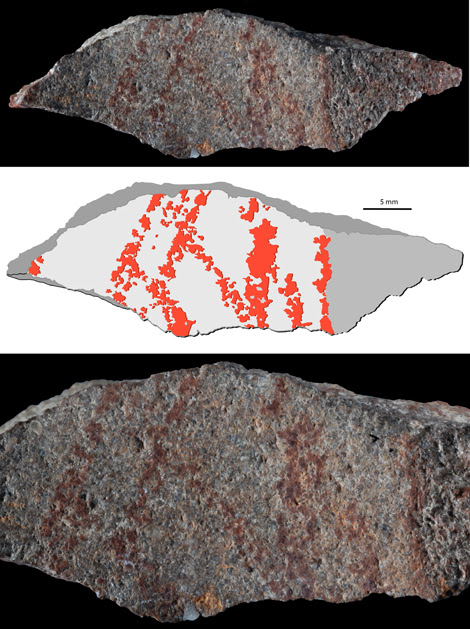

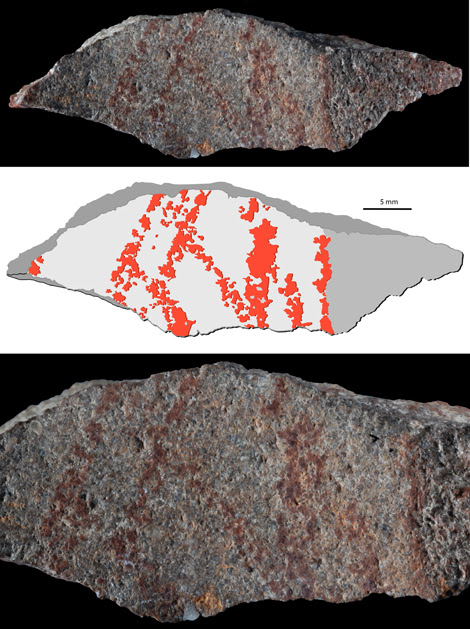

This silcrete flake displays

a drawing made up of nine lines traced on one of its faces with an ocher implement. D'Errico / Henshilwood / Nature

|

Scientists Discover Oldest Drawing

12 September 2018

NRS and the University of the Witwatersrand - The oldest known abstract drawing, made with ocher, has been found in South Africa's Blombos Cave - on the face of a flake of siliceous rock retrieved from archaeological strata dated to 73,000 years before the present. It is a crosshatch of nine lines purposefully traced with a piece of ocher having a fine point and used as a pencil. The work is at least 30,000 years older than the earliest previously known abstract and figurative drawings executed using the same technique. This discovery is reported in Nature (September 12, 2018).

The drawing on the silcrete flake was a surprising find by archaeologist Dr Luca Pollarolo, an honorary research fellow at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits), while he painstakingly sifted through thousands of similar flakes that were excavated from Blombos Cave at the Wits University satellite laboratory in Cape Town.

Blombos Cave has been excavated by Professor Christopher Henshilwood and Dr Karen van Niekerk since 1991. It contains material dating from 100 000 - 70 000 years ago, a time period referred to as the Middle Stone Age, as well as younger, Later Stone Age material dating from 2000 - 300 years ago.

Realizing that the lines on the flake were unlike anything that the team had come across from the cave before, they set out to answer the questions it posed. Were these lines natural, or a part of the matrix of the rock? Were they, perhaps, made by humans living in Blombos Cave 73 000 years ago? If humans made the lines, how did they make them, and why?

Under the guidance of Professor Francesco d'Errico at the PACEA lab of the University of Bordeaux, France (the second author of the paper) the team examined and photographed the piece under a microscope to establish whether the lines were part of the stone or whether it was applied to it. To ensure their results, they also examined the piece by using RAMAN spectroscopy and an electron microscope. After confirming the lines were applied to the stone, the team experimented with various paint and drawing techniques and found that the drawings were made with an ocher crayon or pencil, with a tip of between 1 and 3 millimeters thick. Further, the abrupt termination of the lines at the edge of the flake also suggested that the pattern originally extended over a larger surface, and may have been more complex in its entirety.

"Before this discovery, Palaeolithic archaeologists have for a long time been convinced that unambiguous symbols first appeared when Homo sapiens entered Europe, about 40,000 years ago, and later replaced local Neanderthals," says Henshilwood. "Recent archaeological discoveries in Africa, Europe and Asia, in which members of our team have often participated, support a much earlier emergence for the production and use of symbols."

The earliest known engraving, a zig-zag pattern, incised on a fresh water shell from Trinil, Java, was found in layers dated to 540,000 years ago and a recent article has proposed that painted representations in three caves of the Iberian Peninsula were 64,000 years old and therefore produced by Neanderthals. This makes the drawing on the Blombos silcrete flake the oldest drawing by Homo sapiens ever found.

Although abstract and figurative representations are generally considered conclusive indicators of the use of symbols, assessing the symbolic dimension of the earliest possible graphisms is tricky.

Symbols are an inherent part of our humanity. They can be inscribed on our bodies in the form of tattoos and scarifications or cover them through the application of particular clothing, ornaments and the way we dress our hair.

Language, writing, mathematics, religion, laws could not possibly exist without the typically human capacity to master the creation and transmission of symbols and our ability to embody them in material culture. Substantial progress has been made in understanding how our brain perceives and processes different categories of symbols, but our knowledge on how and when symbols permanently permeated the culture of our ancestors is still imprecise and speculative.

The archaeological layer in which the Blombos drawing was found also yielded other indicators of symbolic thinking, such as shell beads covered with ocher, and, more importantly, pieces of ocher engraved with abstract patterns. Some of these engravings closely resemble the one drawn on the silcrete flake.

"This demonstrates that early Homo sapiens in the southern Cape used different techniques to produce similar signs on different media," says Henshilwood. "This observation supports the hypothesis that these signs were symbolic in nature and represented an inherent aspect of the behaviorally modern world of these African Homo sapiens, the ancestors of all of us today."

Source: https://popular-archaeology.com/article/scientists-discover-oldest-drawing/

|

Portrait of Charles I of Spain, ruler of the Holy Roman Empire

|

Details of horrific first voyages in transatlantic slave trade revealed

17 August 2018

Almost completely ignored by the modern world, this month marks the 500th anniversary of one of history's most tragic and significant events - the birth of the Africa to America transatlantic slave trade. New discoveries are now revealing the details of the trade's first horrific voyages.

Exactly five centuries ago - on 18 August 1518 (28 August 1518, if they had been using our modern Gregorian calendar) - the King of Spain, Charles I, issued a charter authorising the transportation of slaves direct from Africa to the Americas. Up until that point (since at least 1510), African slaves had usually been transported to Spain or Portugal and had then been transhipped to the Caribbean.

Charles's decision to create a direct, more economically viable Africa to America slave trade fundamentally changed the nature and scale of this terrible human trafficking industry. Over the subsequent 350 years, at least 10.7 million black Africans were transported between the two continents. A further 1.8 million died en route.

This month's quincentenary is of a tragic event that caused untold suffering and still today leaves a legacy of poverty, racism, inequality and elite wealth across four continents. But it also quite literally changed the world and still geopolitically, socially, economically and culturally continues to shape it even today - and yet the anniversary has been almost completely ignored.

"There has been a general failure by most historians and others to fully appreciate the huge significance of August 1518 in the story of the transatlantic slave trade," said one of Britain's leading slavery historians, Professor David Richardson of the University of Hull's Wilberforce Institute for the Study of Slavery and Emancipation.

The sad reality is that there currently are only two or three academics worldwide studying the origins of the transatlantic slave trade - and much of our knowledge about it has only been discovered over the past three years.

"The discoveries we've made are transforming our understanding of the very beginnings of the transatlantic slave trade. Remarkably, up till now, it's been a shockingly understudied area," said Professor David Wheat of Michigan State University, a historian who has been closely involved in the groundbreaking research.

In the August 1518 charter, the Spanish king gave one of his top council of state members, Lorenzo de Gorrevod, permission to transport "four thousand negro slaves both male and female" to "the [West] Indies, the [Caribbean] islands and the [American] mainland of the [Atlantic] ocean sea, already discovered or to be discovered", by ship "direct from the [West African] isles of Guinea and other regions from which they are wont to bring the said negros".

Although the charter has been known to historians for at least the past 100 years, nobody until recently knew whether the authorised voyages had ever taken place.

Now new as-yet-unpublished research shows that those royally sanctioned operations did indeed take place with some of the earliest ones occurring in 1519, 1520, May 1521 and October 1521.

These four voyages (all discovered by American historians over the past three years) were from a Portuguese trading station called Arguim (a tiny island off the coast of what is now northern Mauritania) to Puerto Rico in the Caribbean. The first three carried at least 60, 54 and 79 slaves respectively - but it is likely that there were other voyages from Arguim to Hispaniola (modern Haiti and Dominican Republic). The discoveries were made in Spanish archives by two historians - Dr Wheat, of Michigan State, and Dr Marc Eagle, of Western Kentucky University.

It is likely that at least the 1520 voyage - and conceivably also the 1519 one - was by a Portuguese or Spanish caravel called the Santa Maria de la Luz, captained by a mariner called Francisco (or Fernando) de Rosa. The new research also shows that one of the 1521 voyages was by another caravel, the San Miguel, captained by a (probably Basque) sailor called Martin de Urquica, who was acting on behalf of two prominent Seville-based businessmen, Juan Hernandez de Castro and Gaspar Centurion.

The Arguim story had had its genesis more than 70 years earlier when, in 1445, the Portuguese established that trading post so that Portugal could acquire cheaper supplies of gold, gum Arabic and slaves.

By 1455, up to 800 slaves a year were being purchased there and then shipped back to Portugal.

Arguim island was just offshore from a probable coastal slave trade route between a series of slave-trading West African states, who almost certainly sold prisoners-of-war as slaves, and the Arab states of North Africa.

In that sense, the direct transatlantic slave trade that began in 1518/1519 was a by-product of the already long-established Arab slave trade.

However, any reliance on buying slaves from Arab slave trade operations did not last long, for in (or by) 1522, some 2,000 miles southeast of Arguim, direct slave voyages started between the island of Sao Tome off the northwest coast of central Africa and Puerto Rico and probably other Caribbean ports.

Academic research shows that this 1522 voyage carried no fewer than 139 slaves. Another voyage in 1524, discovered in 2016, carried just 18 – plus lots of other non-human merchandise. But other mostly recently discovered voyages in 1527, 1529 and 1530 carried 257, 248 and 231 slaves respectively. On average, therefore, each early voyage from Sao Tome carried much greater numbers of slaves than the ones from Arguim. It’s also likely that there were many other slave voyages between 1518 and 1530 which still await discovery by archival researchers.

There were also at least six early slave voyages from the Cape Verde Islands off the West African coast to the Caribbean between 1518 and 1530, laden with Black African captives acquired by Cape Verdean slave traders mainly from local African rulers and traders in what is now Senegal, Gambia and Guinea-Bissau, Guinea and Sierra Leone.

But, apart from the Spanish king himself, who were the people who launched the direct transatlantic slave trade from Africa to the Caribbean exactly 500 years ago?

The most senior was the man Charles awarded the slave trade charter to in August 1518. He was Laurent de Gouvenot (Lorenzo de Gorrevod in Spanish) - an aristocrat in the Flemish court and member of the Spanish king's council of state (Flanders, predominantly the northern part of modern Belgium, was part of the Burgundian Netherlands, ruled by Charles).

But, for Laurent, the charter was simply a licence from an old chum to make money without actually doing the appalling dirty work himself.

As he was specifically allowed to by the charter, he subcontracted the operations to Juan Lopez de Recalde, the treasurer of the Spanish government agency with responsibility for all Caribbean matters, who in turn sold the rights to transport 3,000 of the 4,000 slaves to a Seville-based Genoese merchant, Agostin de Vivaldi, and his Castilian colleague, Fernando Vazquez, and the right to carry the remaining thousand slaves to another Genoese merchant, Domingo de Fornari.

Vivaldi and Vazquez then (at a profit) resold the rights to transport their 3,000 slaves to two well connected Castilian merchants, Juan de la Torre and Juan Fernandez de Castro, and to a famous Seville-based Genoese banker, Gaspar Centurion, who, along with Fornari, subcontracted the work directly or indirectly to various ships' captains.

All these businessmen had substantial mercantile experience - and Fornari came from a slave-trading family with a long experience of human trafficking in the Eastern Mediterranean.

At least four voyages from Arguin to Puerto Rico were organised and carried out between 1519-1521. It is likely that Vivaldo and Fornet (still probably acting on the basis of Lorenzo de Gorrevod's charter) then, after 1521, hired captains to operate from Sao Tome to Puerto Rico. It is perhaps significant that the first Sao Tome-originating slave voyage to the Caribbean took place in 1522 the year that the Portuguese crown (under the newly enthroned very pro-Spanish Portuguese king, John III) assumed direct control over Sao Tome. This implies that the Spanish and Portuguese crowns may well have been working in close cooperation in the early development of the transatlantic slave trade.

The trade was a catastrophe for Africa. The Arab slave trade had already had a terrible impact on the continent - but European demand for slave labour in their embryonic New World empires worsened the situation substantially. Although many of the slaves for the Arab and transatlantic markets were captured and/or enslaved and sold by African rulers, the European slave traders massively expanded demand - and consequently, in the end, triggered a whole series of terrible intra-African tribal wars.

For, by around the mid-16th century, in order to satisfy European/New World demand, African slave raiders needed more captives to sell as slaves to the Europeans - and that necessitated starting and expanding more raids (and, subsequently, wars) to obtain them. The issuing of the royal charter 500 years ago this month not only led to the kidnapping of millions of people and a lifetime of subjugation and pain for them, but also led to the political and military destabilisation of large swathes of an entire continent.

But this African catastrophe was linked to another terrible human disaster on the American side of the Atlantic, the sheer scale of which is only now being revealed by archaeology. For the main reason that the Europeans needed African slaves to be shipped to the Caribbean was because the early Spanish colonisation of that region had led to the deaths of up to three million local Caribbean Indians, many of whom the Spanish had already de facto enslaved and had intended to be their local workforce.

When Columbus had discovered Hispaniola in 1492, the island had probably had a population of at least two million. By 1517, this had been reduced by at least 80 per cent - due to European-introduced epidemics (the Indians had no immunity), warfare, massacres, starvation and executions. Many of the surviving Indians had also fled into Hispaniola's mountainous interior where they were beyond the reach of the Spanish state. Ongoing archaeological investigations on the island are only now revealing the sheer scale of its pre-Columbian population.

The reality was that, by 1514, according to a government census, there were only 26,000 Indians left under Spanish control - and the Spanish feared that number would further reduce. It was this population collapse and the fear that it would continue that appears to have forced the Spanish king to, for the first time, authorise direct slave shipments from Africa to the Americas. Spain was desperate to ensure that its royal goldmines and agricultural estates in Hispaniola and its economic projects on the other Caribbean islands would not founder for lack of manpower.

Source:

|

An ancient human skull from Jebel Irhoud - Ryan Somma / Flickr / Katie Martin / The Atlantic)

|

The New Story of Humanity's Origins in Africa

11 July 2018

There is a decades-old origin story for our species, in which we descended from a group of hominids who lived somewhere in Africa around 200,000 years ago. Some scientists have placed that origin in East Africa; others championed a southern birthplace. In either case, the narrative always begins in one spot. Those ancestral hominids, probably Homo heidelbergensis, slowly accumulated the characteristic features of our species - the rounded skull, small face, prominent chin, advanced tools, and sophisticated culture. From that early cradle, we then spread throughout Africa, and eventually the world.

But some scientists are now arguing that this textbook narrative is wrong in its simplicity, linearity, and geography. Yes, we evolved from ancestral hominids in Africa, but we did it in a complicated fashion - one that involves the entire continent.

Consider the ancient human fossils from a Moroccan cave called Jebel Irhoud, which were described just last year. These 315,000-year-old bones are the oldest known fossils of Homo sapiens. They not only pushed back the proposed dawn of our species, but they added northwest Africa to the list of possible origin sites. They also had an odd combination of features, combining the flat faces of modern humans with the elongated skulls of ancient species like Homo erectus. From the front, they could have passed for us; from the side, they would have stood out.

Fossils from all over Africa have modern and ancient traits in varied combinations, including the 260,000-year-old Florisbad skull from South Africa; the 195,000-year-old remains from Omo Kibish in Ethiopia; and the 160,000-year-old Herto skull, also from Ethiopia. Some scientists have argued that these remains represent different subspecies of Homo sapiens, or different species altogether.

But perhaps they really were all Homo sapiens, and our species simply used to be far more diverse than we currently are. "If you look at skulls, you'll see different features of modern humans arising in different locations at different times," says Eleanor Scerri, an archaeologist at the University of Oxford. And the reason for that, she says, is that "we're a species with multiple African origins."

She and others argue that humans originated from several diverse populations that lived across Africa. Separated from each other by geographical barriers, they mostly evolved in isolation, and each group developed some of our hallmark traits, but not others. But their separation wasn't constant: As a changing climate remodeled the African landscape, greening deserts and drying out forests, those early humans were repeatedly drawn together and pulled apart. Whenever they met, they mated and mingled, exchanging genes and ideas in a continent-wide melting pot that eventually coalesced into the full bingo of features that you or I might recognize.

This theory, known as "African multiregionalism," is a fundamentally different view of how we came to be. It's saying that no single place or population gave rise to us. It's saying that the cradle of humankind was the entirety of Africa.

Scerri recently convened with 22 other anthropologists, archaeologists, geneticists, and climatologists in London to review the evidence for African multiregionalism. Their discussions are described in a paper that is published today, and that Mark Thomas, a co-author, describes as a call to arms. "We're saying that it's extremely unlikely that humans evolved in one location and then spread throughout the world," he says. "Our ancestry will have reached to many, many corners of Africa."

"It's a good paper and I definitely agree," says Louise Leakey, who has long studied hominid fossils in East Africa. "The numerous finds that have emerged from different sites in Africa [suggest] a patchwork of highly structured populations living across the continent."

This can be a tricky concept to grasp, because we're so used to thinking about ancestry in terms of trees, whether it's a family tree that unites members of a clan or an evolutionary tree that charts the relationships between species. Trees have single trunks that splay out into neatly dividing branches. They shift our thoughts toward single origins. Even if humans were widespread throughout Africa 300,000 years ago, surely we must have started somewhere.

Not so, according to the African-multiregionalism advocates. They're arguing that Homo sapiens emerged from an ancestral hominid that was itself widespread through Africa, and had already separated into lots of isolated populations. We evolved within these groups, which occasionally mated with each other, and perhaps with other contemporaneous hominids like Homo naledi.

The best metaphor for this isn't a tree. It's a braided river - a group of streams that are all part of the same system, but that weave into and out of each other.

These streams eventually merge into the same big channel, but it takes time - hundreds of thousands of years. For most of our history, any one group of Homo sapiens had just some of the full constellation of features that we use to define ourselves. "People back then looked more different to each other than any populations do today," says Scerri, "and it's very hard to answer what an early Homo sapiens looked like. But there was then a continent-wide trend to the modern human form." Indeed, the first people who had the complete set probably appeared between 40,000 and 100,000 years ago.

Our behavior likely evolved in the same patchwork way. For a few million years, hominids made the same style of large stone handaxes from one millennium to the next. But that technological stagnation ended around 300,000 years ago - the same age as the earliest Homo sapiens fossils. From that time period, archeologists have recovered new kinds of specialized and sophisticated stone tools, like awls and spear tips.

These tools of the so-called Middle Stone Age show that the modern human mind developed at roughly the same time as the modern human body. And they hint that this transition happened at a continental scale, for such tools have been found at Jebel Irhoud in Morocco, at Olorgesaillie in Kenya, and at Florisbad in South Africa, with regional differences at each site.

There's one large potential problem with the African multiregionalism story. Genetic studies of today's African populations suggest that they diverged from one another between 100,000 and 150,000 years ago - far later than the early, continent-wide origin suggested by the bones and tools. That deep and broad origin might be right, "but, it's not something that we geneticists have formally tested," says Brenna Henn from UC Davis, who is an author on the new paper. “We have discussed ways of doing that, but there's no published paper yet saying that there is deep population structure in Africa."

But the DNA of today's Africans has been shaped by more recent population upheavals that have obscured the goings-on of 300,000 years ago. What's more, the studies that analyzed this modern DNA have largely relied on tree-like population models in which a single lineage grows from a single place - exactly the scenario that proponents of African multiregionalism say is wrong. "In science, we use simple models for good reasons, because often we don't have sufficient data to inform more complex models," says Thomas, who is a geneticist himself. "But there's a difference between using simple models and believing in them."

"We're just at the beginning of trying to figure out how to refine this new theory," says Scerri. "To know more about what happened, we need to get more data from many of the gaps in Africa. The earliest Homo sapiens fossils we have come from 10 percent of Africa, and we're extrapolating to 90 percent of the continent. Most of it remains unexplored. We're effectively saying those places aren't worth looking at because we have the answer from 10 percent. How can we possibly know that?"

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/07/the-new-story-of-humanitys-origins/564779/

|

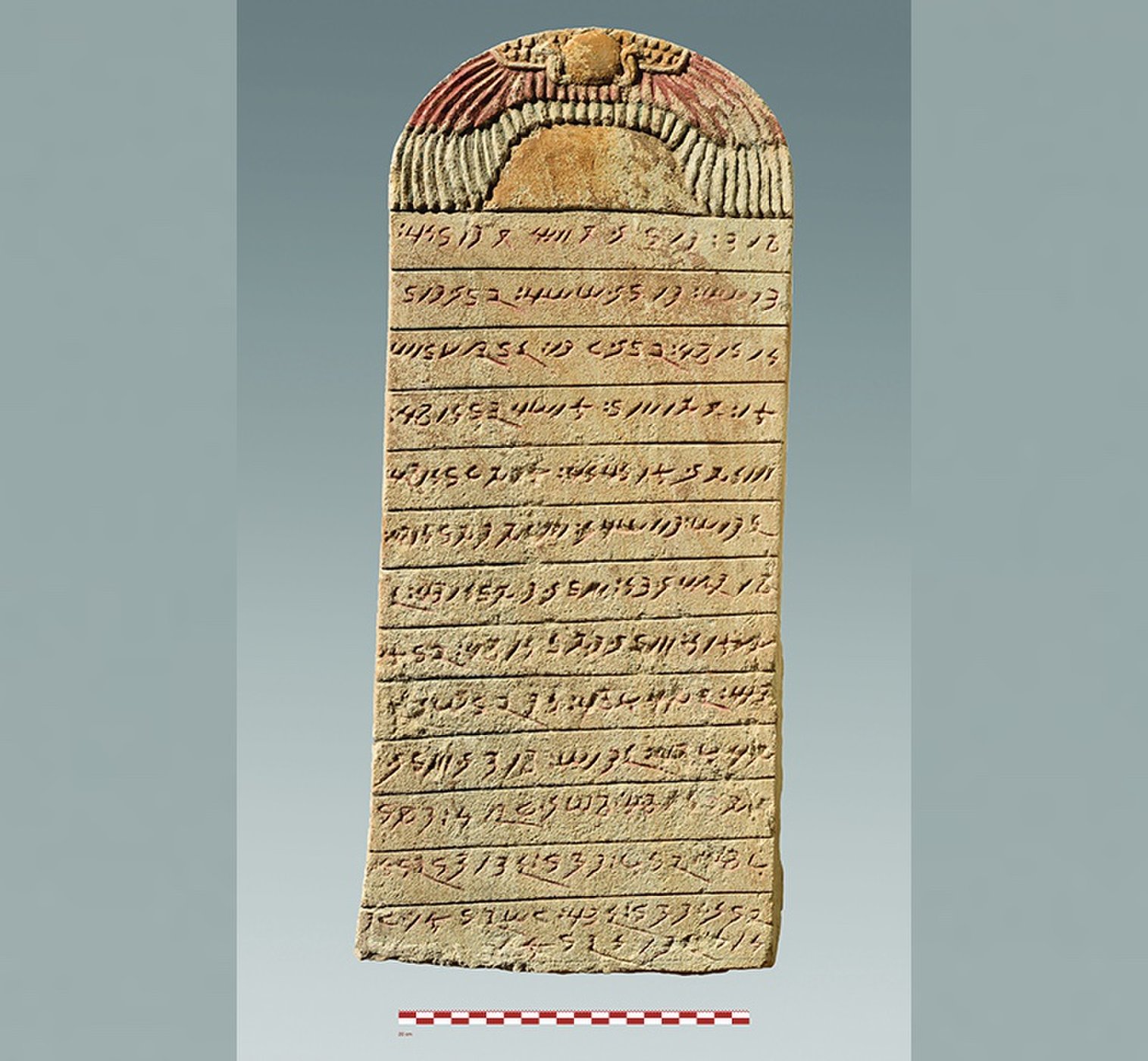

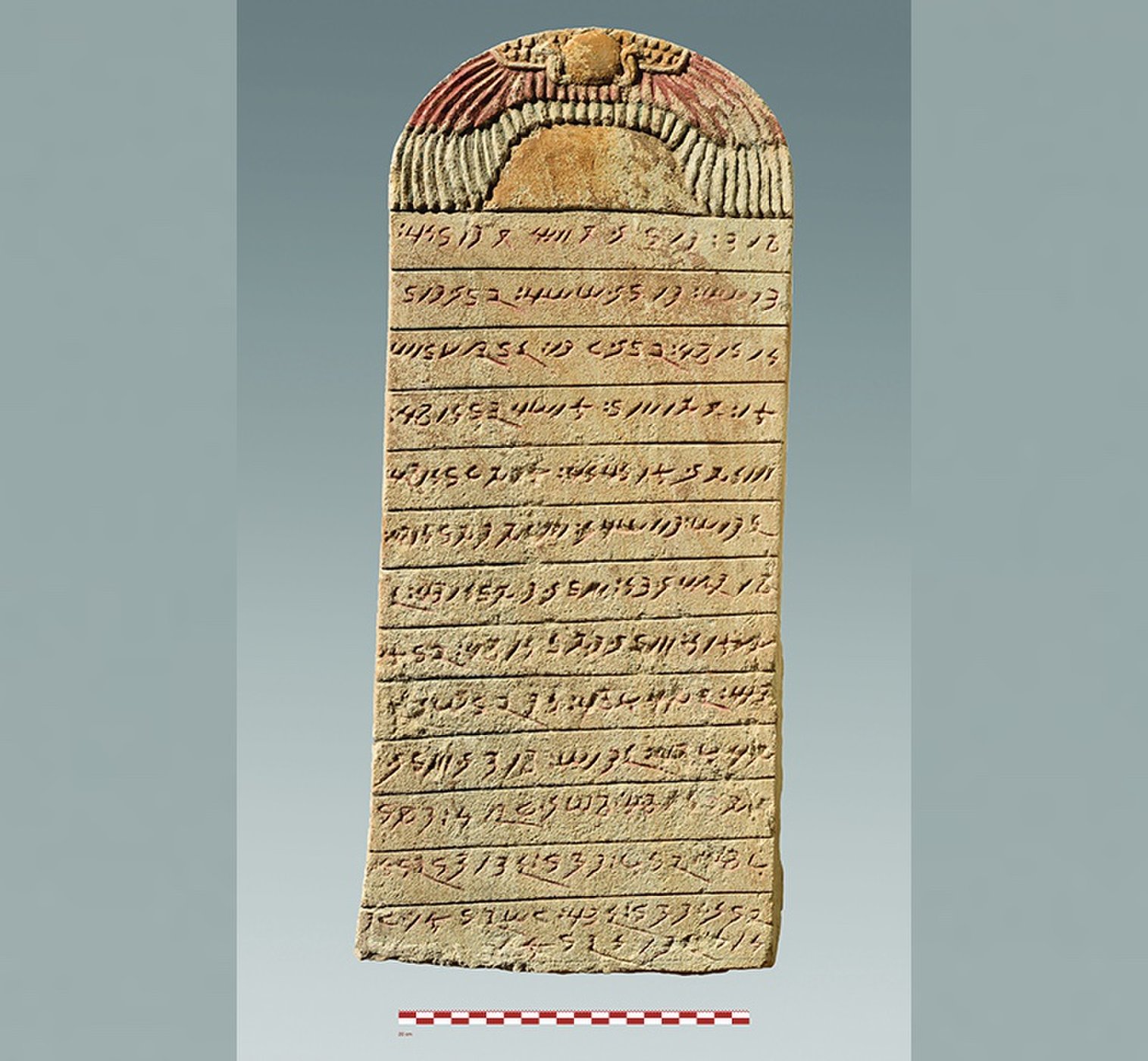

This Ataqeloula stele was discovered in November

2017 at the Sedeinga necropolis, which commemorates a woman from Sedeinga high society and prestigious members

of her family.

Credit: Vincent Francigny /

Sedeinga archaeological mission

|

Nubian Stone Tablets Unearthed in African 'City of the Dead'

11 April 2018

A huge cache of stone inscriptions from one of Africa's oldest written languages have been unearthed in a vast "city of the dead" in Sudan.

The inscriptions are written in the obscure 'Meroitic' language, the oldest known written language south of the Sahara, which has been only partly deciphered.

The discovery includes temple art of Maat, the Egyptian goddess of order, equity and peace, that was, for the first time, depicted with African features.

Ancient civilization of Meroe

Scientists investigated the archaeological site of Sedeinga, located on the western shore of the Nile River in Sudan, about 60 miles (100 kilometers) north of the river's third "cataract," or set of shallows.

Archaeologists first heard of the site from the tales of 19th-century travelers, who described the remains of the Egyptian temple of Queen Tiye, the chief wife of Amenhotep III and one of the most illustrious queens of ancient Egypt, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. Amenhotep III's reign from about 1390 B.C. to 1353 B.C. marked the zenith of ancient Egyptian civilization - in both political power and cultural achievement, according to the BBC.

The sandy area was once part of ancient Nubia, known for rich deposits of gold. Nubia hosted some of Africa's earliest kingdoms, and a few even ruled Egypt as pharaohs, according to the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago.

The site of Sedeinga is home to a large necropolis, known as the "city of the dead," stretching more than 60 acres (25 hectares). It holds the vestiges of at least 80 brick pyramids and more than 100 tombs from the kingdoms of Napata and Meroe, which lasted from the seventh century B.C. to the fourth century A.D. These kingdoms mixed the cultures of Egypt and the rest of Africa in ways still seen in Sudan today, researchers said.

Napata and Meroe formed a civilization known as the kingdom of Kush by their ancient Egyptian neighbors. Meroitic, the language of Meroe, borrowed written characters from ancient Egyptian.

"The Meroitic writing system, the oldest of the sub-Saharan region, still mostly resists our understanding," Vincent Francigny, an archaeologist at the French Archaeological Unit Sudan Antiquities Service, and co-director of the Sedeinga excavation, told Live Science. "While funerary texts, with very few variations, are quite well-known and can be almost completely translated, other categories of texts often remain obscure. In this context, every new text matters, as they can shed light on something new."

Huge cache of inscriptions

Now, the scientists revealed they have unearthed the largest collection of Meroitic texts yet. The inscriptions are funerary in nature.

"Every text tells a story - the name of the deceased and both parents, with their occupations sometime; their career in the administration of the kingdom, including place names; their relation to extended family with prestigious titles," Francigny said.

From these inscriptions, "we can, for example, locate new places, or guess their possible locations, or learn about the structure of the religious and royal administration in the provinces of the kingdom," Francigny said. The texts "also tell us what kind of town or settlement was connected to the cemetery we are excavating," he said.

Based on evidence from texts, the site's context, and numerous imported goods found in the graves there, the researchers think Sedeinga was a key place for commercial roads that avoided the meandering and the cataracts of the Nile to the north "to go straight to Egypt through desert roads," Francigny said. "The town would have developed and become wealthy around this activity."

The researchers also discovered numerous samples of decorated sandstone, including chapel art depicting the Egyptian goddess Maat with Nubian features.

"Meroe was a kingdom where, among others, some Egyptian cultural and religious concepts were borrowed and adapted to local traditions," Francigny said. "We should not see Meroe as a passive recipient for foreign influences - instead, Meroites were very selective about what they could borrow to serve the purpose of the royal family and the development of their pharaonic, but non-Egyptian, society."

High-ranking women

The scientists noted that a number of artifacts at Sedeinga were dedicated to high-ranking women. For instance, one stele - an upright decorated slab of stone - in the name of a Lady Maliwarase described her as the sister of two grand priests of Amon, and as having a son who held the position of governor of Faras, a large city bordering the second cataract of the Nile. In addition, a tomb inscription described a Lady Adatalabe, who hailed from an illustrious lineage that included a royal prince.

In Nubia, a matrilineal society, the tracing of one's descent through the female line was "an important aspect in royal family lineages," Francigny said. For instance, "at Meroe, with the figure of the 'candace,' a sort a queen mother, women could, in the royal context, play an important role and be associated with the exercise of power. It is unclear if, at a lower level, women could also play key roles in the administration of the kingdom and the religious sphere."

Intriguingly, on several occasions at archaeological sites related to the kingdom of Meroe, the scientists noted that Meroites were sometimes fascinated with random items with unusual shapes.

"For example, near temples where only priests could enter, it is not unusual to find places made for popular offerings; these offerings were sometime made of oddly shaped natural stones that seemed supernatural because their shapes look like religious symbols or anatomical parts of the human body," Francigny said. "We even found some inside of the most sacred room, the 'naos,' of some Meroitic temples, near the statues of the gods."

In the future, the researchers hope to locate graves dating back to the earliest stages of the site, "during Egyptian colonization," Francigny said. "Unfortunately, in this region the Nile moves toward the east," and so slowly eats away at the excavation site, "which means that there is likely a chance that the settlement that was close to the river was completely destroyed," he said.

Source: https://www.livescience.com/62272-oldest-meroe-inscriptions-sudan-africa.html

|

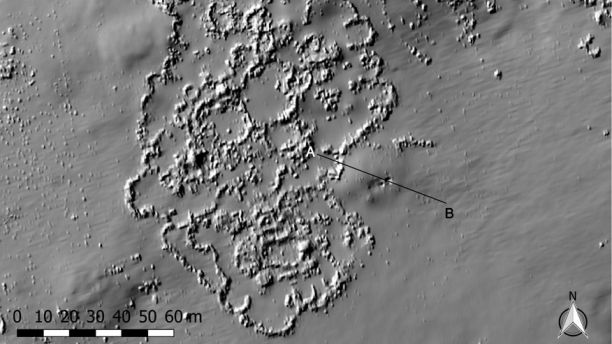

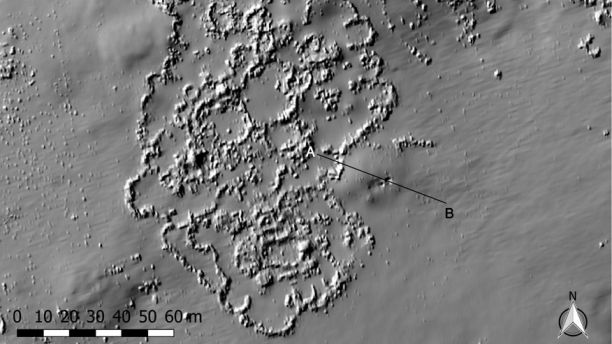

Lidar imagery of SKBR (Karim Sadr)

|

'Lost city' revealed in South Africa using laser technology

22 March 2018

Archaeologists in South Africa have located the site of a centuries-old 'lost city' using sophisticated laser technology.

Local landowners had known about ruins at Suikerbosrand near Johannesburg for generations, according to Karim Sadr, professor at the School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand. "Archaeologists from my University dug several of the homesteads there in the 1970s and 1980s," he told Fox News, via email. "But no one ever saw the ruins as anything more than a scatter of homesteads, a few villages dispersed here and there."

Sadr, who has visited the area multiple times in the past three decades, explained that he used LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology to reveal the city's secrets. The in-depth aerial images tell a fascinating story of the archaeological site, which is known as 'SKBR.'

"It is only when I obtained LiDAR imagery for about 20 square kilometres (7.72 square miles) of the western foothills and had examined it in minute detail that I started to see the aspects of the built environment that are largely invisible from the ground and on air photos because of the vegetation cover," he said. A host of stone structures showed up on the images.

LiDAR uses a laser to measure distances to the Earth's surface and can prove extremely valuable to study what is hidden in areas with thick vegetation. LiDAR is also used extensively in other applications, including autonomous cars where it allows vehicles to have a continuous 360 degrees view.

Sadr commissioned a LiDAR aerial survey of the first 10 square kilometres in late 2014 and the remainder the following year. "It was only in 2016 after poring over all of that detailed imagery that I eventually realized that the homesteads are not a scatter of villages but parts of one entity; a city, rather than a dispersion of homesteads," he told Fox News.

The Conversation reports that the city was occupied by speakers of the Tswana language from the 15th century until about 200 years ago. Other Tswana cities were known to exist in the region, but not in that specific area. The Tswana city-states collapsed as a result of early 19th-century civil war, according to The Conversation.

"It is significant because we did not know that there was a Tswana city this far east of the group that had already been visited by the European travellers at the beginning of the 19th century; so we have extended the range of this archaeological culture and its city-states," said Sadr.

SKBR covered an area of about 6.2 miles from north to south and was about 1.2 miles to 2 miles wide. "I have counted about 800 homesteads in this area and there are probably more, but it is difficult to say how many people occupied the city at any time, since not all the homesteads would have been occupied concurrently and some may have contained many more people than others," Sadr said. "My guess is that the city never had more than 10,000 people at any one time, but that is just an educated guess.”

While more LiDAR coverage of SKBR is planned, archaeologists are also preparing to examine the site up close. "LiDAR cannot show everything and many of the parts of the city need to investigated on the ground from up close," said Sadr, noting that this research can form the basis of students' theses. "Eventually we will want to excavate some parts of the site and since the deposits are not generally deep, not a lot of earth has to be moved."

"Beyond SKBR, there are also questions about the spatial limits of this city-state, its boundaries, outpost, neighbours, external trade connections and such that need to be answered," he added. "And eventually, the big question to answer is why did the Tswana decide to become an urban population around a quarter of a millennium ago?"

Source: http://www.foxnews.com/science/2018/03/22/lost-city-revealed-in-south-africa-using-laser-technology.html

|

A Takarkori rock shelter. University of Huddersfield

|

Entomologist confirms first Saharan farming 10,000 years ago

17 March 2018

By analyzing a prehistoric site in the Libyan desert, a team of researchers from the universities of Huddersfield, Rome and Modena & Reggio Emilia has been able to establish that people in Saharan Africa were cultivating and storing wild cereals 10,000 years ago. In addition to revelations about early agricultural practices, there could be a lesson for the future, if global warming leads to a necessity for alternative crops.

The importance of the find came together through a well-established official collaboration between the University of Huddersfield and the University of Modena & Reggio Emilia.

The team has been investigating findings from an ancient rock shelter at a site named Takarkori in south-western Libya. It is desert now, but earlier in the Holocene age[our present age], some 10,000 years ago, it was part of the "green Sahara" and wild cereals grew there. More than 200,000 seeds - in small circular concentrations - were discovered at Takarkori, which showed that hunter-gatherers developed an early form of agriculture by harvesting and storing crops.

But an alternative possibility was that ants, which are capable of moving seeds, had been responsible for the concentrations. Dr Stefano Vanin, the University of Huddersfield's Reader in Forensic Biology and a leading entomologist in the forensic and archaeological fields, analyzed a large number of samples, now stored at the University of Modena & Reggio Emilia. His observations enabled him to demonstrate that insects were not responsible and this supports the hypothesis of human activity in collection and storage of the seeds.

The investigation at Takarkori provides the first-known evidence of storage and cultivation of cereal seeds in Africa. The site has yielded other key discoveries, including the vestiges of a basket, woven from roots, that could have been used to gather the seeds. Also, chemical analysis of pottery from the site demonstrates that cereal soup and cheese were being produced.

A new article that describes the latest findings and the lessons to be learned appears in the journal Nature Plants. Titled Plant behaviour from human imprints and the cultivation of wild cereals in Holocene Sahara, it is co-authored by Anna Maria Mercuri, Rita Fornaciari, Marina Gallinaro, Savino di Lernia and Dr Vanin.

One of the article's conclusions is that although the wild cereals, harvested by the people of the Holocene Sahara, are defined as "weeds" in modern agricultural terms, they could be an important food of the future.

"The same behavior that allowed these plants to survive in a changing environment in a remote past makes them some of the most likely possible candidates as staple resources in a coming future of global warming. They continue to be successfully exploited and cultivated in Africa today and are attracting the interest of scientists searching for new food resources," state the authors.

Research based on the findings at Takarkori continues. Dr Vanin is supervising PhD student Jennifer Pradelli - one of a cohort of doctoral candidates at the University of Huddersfield funded by a €1 million award from the Leverhulme Trust - and she is analyzing insect evidence in order to learn more about the evolution of animal breeding at the site.

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/winter-2018/article/entomologist-confirms-first-saharan-farming-10-000-years-ago

|

Tooling down: By around 320,000 years ago in

East Africa, Homo sapiens

or a close relative had shifted from making large chopping implements (left) to fashioning spearpoints

and other small tools

(right).

|

Ancient climate shifts may have sparked human ingenuity and networking

15 March 2018

Dramatic shifts in the East African climate may have driven toolmaking advances and the development of trading networks among Homo sapiens or their close relatives by the Middle Stone Age, roughly 320,000 years ago. That's the implication of discoveries reported in three papers published online March 15 in Science.

Newly excavated Middle Stone Age tools and red pigment chunks from southern Kenya's Olorgesailie Basin appear to have been part of a long trend of climate-driven behavior changes in members of the Homo genus that amped up in H. sapiens. Locations of food sources can vary unpredictably on changing landscapes. H. sapiens and their precursors responded by foraging over larger areas with increasingly smaller tools, the researchers propose. Obsidian used for the Middle Stone Age tools came from far away, raising the likelihood of long-distance contacts and trading among hominid populations near humankind's root.

At roughly 320,000 years old, the excavated Middle Stone Age tools are the oldest of their kind, paleoanthropologist Rick Potts and colleagues report in one of the new papers. Researchers had previously estimated that such tools - spearpoints and other small implements struck from prepared chunks of stone - date to no earlier than 280,000 to possibly 300,000 years ago. Other more primitive, handheld cutting stones made of local rock date from around 1.2 million to 499,000 years ago at Olorgesailie. Gradual downsizing of those tools, including oval hand axes, occurred from 615,000 to 499,000 years ago, a stretch characterized by frequent shifts between wet and dry conditions, the scientists say.

It's not known whether that tool trend continued or if a sudden transition to Middle Stone Age implements happened between 499,000 and 320,000 years ago. Erosion at Olorgesailie artifact sites has destroyed sediment from that time period, leaving the nature of toolmaking during that time gap a mystery. Age estimates relied on measures of the decay of radioactive forms of argon and uranium in volcanic ash layers framing tool-bearing sediment. It's unclear whether Homo sapiens or a closely related species made Olorgesailie's Middle Stone Age tools, since no hominid fossils have been found there.

Back-and-forth shifts from dry to wet conditions - many happening over only a few years or decades - continued to regularly reshape the Olorgesailie landscape around 320,000 years ago, conclude Potts, of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and colleagues in another of the new papers. That timing coincides roughly with the emergence of H. sapiens (SN: 12/23/17, p. 24). The team's climate reconstruction is based on microscopic and chemical analyses of the region's soil.

A substantial number of Olorgesailie's Middle Stone Age tools are made from obsidian that came from at least 25 to 50 kilometers away from the excavation sites. At one Olorgesailie site in particular, 42 percent of more than 3,400 stone artifacts were obsidian. Some of those finds display signs of having been attached to handles, likely as spearpoints, a group led by archaeologist Alison Brooks of George Washington University in Washington, D.C., reports in the third paper. Brooks is also a coauthor on the other studies.

Formation of trading networks among dispersed groups of H. sapiens, or possibly among closely related populations, best explains how large amounts of obsidian turned up at Olorgesailie by 320,000 years ago, contends Potts, who coauthored the third paper. "Social networking during a long period of climate variability was a key to success for early Homo sapiens," he says. "Greater mobility encouraged inventive thinking about how to acquire resources." Potts has long argued that H. sapiens and close evolutionary relatives evolved to deal with constantly changing environments (SN: 8/20/05, p. 116).

Still, factors other than climate fluctuations, such as hominid population declines or surges, may also have spurred ancient tool innovations to acquire more or different types of food, cautions archaeologist Yonatan Sahle of the University of Tübingen in Germany.

In addition to the obsidian tools, a total of 88 pigment lumps, including two pieces with grinding marks, came from an undetermined distance outside the Olorgesailie vicinity, Brooks' group says. Pigment applied to one's body or belongings may have signaled group identity or social status, the researchers suggest.

The new reports fit with genetic evidence that H. sapiens originated in Africa between 350,000 and 260,000 years ago (SN: 10/28/17, p. 16), says Stone Age archaeologist Marlize Lombard of the University of Johannesburg. Smaller, more specialized Middle Stone Age tools appearing along with pigment "provide strong indicators that by around 300,000 years ago we were well on our way to becoming modern humans in Africa," she holds.

Ancient toolmaking approaches varied greatly from one part of Africa to another, with hominids employing diverse mixes of old-school chopping tools and newer, sharp points, says archaeologist John Shea of Stony Brook University in New York. At Olorgesailie and elsewhere, he says, "early Homo sapiens and their immediate African ancestors were at least as smart as the scientists investigating them."

Source: https://www.sciencenews.org/article/ancient-climate-shifts-may-have-sparked-human-ingenuity-and-networking

|

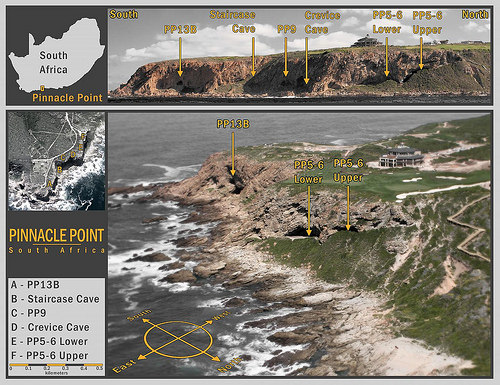

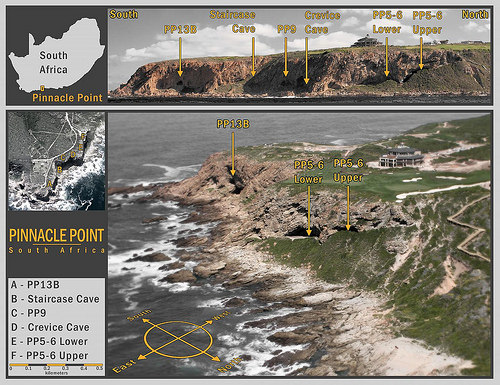

The research team has

been excavating caves at Pinnacle Point, South

Africa, for nearly 20 years. Glass shards from Mount Toba were discovered at

the PP5-6 location. Erich Fisher

|

Humans thrived in South Africa through the Toba super-volcanic eruption ~ 74,000 years ago

11 March 2018

Imagine a year in Africa when summer never arrives. The sky takes on a gray hue during the day and glows red at night. Flowers do not bloom. Trees die in the winter. Large mammals like antelope become thin, starve and provide little fat to the predators (carnivores and human hunters) that depend on them. Then, this same disheartening cycle repeats itself, year after year. This is a picture of life on earth after the eruption of the super-volcano, Mount Toba in Indonesia, about 74,000 years ago. In a paper* published this week in Nature, scientists show that early modern humans on the coast of South Africa thrived through this event.

An eruption a hundred times smaller than Mount Toba - that of Mount Tambora, also in Indonesia, in 1815 - is thought to have been responsible for a year without summer in 1816. The impact on the human population was dire - crop failures in Eurasia and North America, famine and mass migrations. The effect of Mount Toba, a super-volcano that dwarfs even the massive Yellowstone eruptions of the deeper past, would have had a much larger, and longer-felt, impact on people around the globe.

The scale of the ash-fall alone attests to the magnitude of the environmental disaster. Huge quantities of aerosols injected high into the atmosphere would have severely diminished sunlight - with estimates ranging from a 25 to 90 percent reduction in light. Under these conditions, plant die-off is predictable, and there is evidence of significant drying, wildfires and plant community change in East Africa just after the Toba eruption.

If Mount Tambora created such devastation over a full year - and Tambora was a hiccup compared to Toba - we can imagine a worldwide catastrophe with the Toba eruption, an event lasting several years and pushing life to the brink of extinctions.

In Indonesia, the source of the destruction would have been evident to terrified witnesses - just before they died. However, as a family of hunter-gatherers in Africa 74,000 years ago, you would have had no clue as to the reason for the sudden and devastating change in the weather. Famine sets in and the very young and old die. Your social groups are devastated, and your society is on the brink of collapse.

The effect of the Toba eruption would have certainly impacted some ecosystems more than others, possibly creating areas - called refugia - in which some human groups did better than others throughout the event. Whether or not your group lived in such a refuge would have largely depended on the type of resources available. Coastal resources, like shellfish, are highly nutritious and less susceptible to the eruption than the plants and animals of inland areas.

When the column of fire, smoke and debris blasted out the top of Mount Toba, it spewed rock, gas and tiny microscopic pieces (cryptotephra) of glass that, under a microscope, have a characteristic hook shape produced when the glass fractures across a bubble. Pumped into the atmosphere, these invisible fragments spread across the world.

Panagiotis (Takis) Karkanas, director of the Malcolm H. Wiener Laboratory for Archaeological Science, American School of Classical Studies, Greece, saw a single shard of this explosion under a microscope in a slice of archaeological sediment encased in resin.

"It was one shard particle out of millions of other mineral particles that I was investigating. But it was there, and it couldn't be anything else," says Karkanas.

The shard came from an archaeological site in a rockshelter called Pinnacle Point 5-6, on the south coast of South Africa near the town of Mossel Bay. The sediments dated to about 74,000 years ago.

"Takis and I had discussed the potential of finding the Toba shards in the sediments of our archaeological site, and with his eagle eye, he found one," explains Curtis W. Marean, project director of the Pinnacle Point excavations. Marean is the associate director of the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University and honorary professor at the Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience at Nelson Mandela University, South Africa.

Marean showed the shard image to Eugene Smith, a volcanologist with the University of Nevada at Las Vegas, and Smith confirmed it was a volcanic shard.

"The Pinnacle Point study brought me back to the study of glass shards from my master's thesis 40 years earlier," says Smith.

Early in the study, the team brought in expert cryptotephra scientist Christine Lane who trained graduate student Amber Ciravolo in the needed techniques. Racheal Johnsen later joined Ciravalo as lab manager and developed new techniques.

From scratch, with National Science Foundation support, they developed the Cryptotephra Laboratory for Archaeological and Geological Research, which is now involved in projects not only in Africa, but in Italy, Nevada and Utah.

Encased in that shard of volcanic glass is a distinct chemical signature, a fingerprint that scientists can use to trace to the killer eruption. In their paper in Nature, the team describes finding these shards in two archaeological sites in coastal South Africa, tracing those shards to Toba through chemical fingerprinting and documenting a continuous human occupation across the volcanic event.

"Many previous studies have tried to test the hypothesis that Toba devastated human populations," Marean notes. "But they have failed because they have been unable to present definitive evidence linking a human occupation to the exact moment of the event."

Most studies have looked at whether or not Toba caused environmental change. It did, but such studies lack the archaeological data needed to show how Toba affected humans.

The Pinnacle Point team has been at the forefront of development and application of highly advanced archaeological techniques. They measure everything on site to millimetric accuracy with a "total station," a laser-measurement device integrated to handheld computers for precise and error-free recording.

Naomi Cleghorn with the University of Texas at Arlington, recorded the Pinnacle Point samples as they were removed.

Cleghorn explains, "We collected a long column of samples - digging out a small amount of sediment from the wall of our previous excavation. Each time we collected a sample, we shot its position with the total station."

The sample locations from the total station and thousands of other points representing stone artifacts, bone, and other cultural remains of the ancient inhabitants were used to build digital models of the site.

"These models tell us a lot about how people lived at the site and how their activities changed through time," say Erich Fisher, associate research scientist with the Institute of Human Origins, who built the detailed photorealistic 3D models from the data. "What we found was that during and after the time of the Toba eruption people lived at the site continuously, and there was no evidence that it impacted their daily lives."

In addition to understanding how Toba affected humans in this region, the study has other important implications for archaeological dating techniques. Archaeological dates at these age ranges are imprecise - 10 percent (or 1000s of years) error is typical. Toba ash-fall, however, was a very quick event that has been precisely dated. The time of shard deposition was likely about two weeks in duration - instantaneous in geological terms.

"We found the shards at two sites," explains Marean. "The Pinnacle Point rockshelter (where people lived, ate, worked and slept) and an open air site about 10 kilometers away called Vleesbaai. This latter site is where a group of people, possibly members of the same group as those at Pinnacle Point, sat in a small circle and made stone tools. Finding the shards at both sites allows us to link these two records at almost the same moment in time."

Not only that, but the shard location allows the scientists to provide an independent test of the age of the site estimated by other techniques. People lived at the Pinnacle Point 5-6 site from 90,000 to 50,000 years ago. Zenobia Jacobs with the University of Wollongong, Australia, used optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) to date 90 samples and develop a model of the age of all the layers. OSL dates the last time individual sand grains were exposed to light.

"There has been some debate over the accuracy of OSL dating, but Jacobs' age model dated the layers where we found the Toba shards to about 74,000 years ago - right on the money," says Marean. This lends very strong support to Jacobs' cutting-edge approach to OSL dating, which she has applied to sites across southern Africa and the world.

"OSL dating is the workhorse method for construction of timelines for a large part of our own history. Testing whether the clock ticks at the correct rate is important. So getting this degree of confirmation is pleasing," says Jacobs.

In the 1990s, scientists began arguing that this eruption of Mount Toba, the most powerful in the last two million years, caused a long-lived volcanic winter that may have devastated the ecosystems of the world and caused widespread population crashes, perhaps even a near-extinction event in our own lineage, a so-called bottleneck.

This study shows that along the food-rich coastline of southern Africa, people thrived through this mega-eruption, perhaps because of the uniquely rich food regime on this coastline. Now other research teams can take the new and advanced methods developed in this study and apply them to their sites elsewhere in Africa so researchers can see if this was the only population that made it through these devastating times.

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/winter-2018/article/humans-thrived-in-south-africa-through-the-toba-super-volcanic-eruption-74-000-years-ago

|

Aerial photo of the dig in December 2017. Credit: Vincent Francigny /

Sedeinga archaeological mission

|

Archaeologists unearth tombs in ancient Nubia

5 March 2018

The archaeological site of Sedeinga is located in Sudan, a hundred kilometers to the north of the third cataract of the Nile, on the river's western shore. Known especially for being home to the ruins of the Egyptian temple of Queen Tiye, the royal wife of Amenhotep III, the site also includes a large necropolis containing sepulchers dating from the kingdoms of Napata and Meroe (seventh century BCE-fourth century CE), a civilization (1) mixing local traditions and Egyptian influences. Tombs, steles, and lintels have just been unearthed by an international team led by researchers from the CNRS and Sorbonne Université as part of the French Section of Sudan's Directorate of Antiquities, co-funded by the CNRS and the Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs (2). They represent one of the largest collections of Meroitic inscriptions, the oldest language of black Africa currently known.

The necropolis of Sedeinga stretches across more than twenty-five hectares and is home to the vestiges of at least eighty brick pyramids and over a hundred tombs, dating from the kingdoms of Napata and Meroe (seventh century BCE-fourth century CE). The research programs carried out since 2009 (3) have focused on the chronology of the construction of this necropolis, which is difficult as there is very little remaining historical information on this civilization. The researchers have shown that most of the pyramids and tombs are buildings dating from the era of the Napata kingdom that were later adjusted by the Meroitics. These adjustments were thus made five centuries after the initial building on the site, which the Meroitics supplemented with new chapels built out of brick and sandstone blocks on the western side of the pyramids, and which were intended for the worship of the deceased. This practice was particular to the Napatans and Meroitics, who veritably revered the monuments of the past, unlike their Egyptian neighbors.

Pieces of decorated sandstone, such as steles as well as lintels and door surrounds, have been discovered at the surface, providing magnificent examples of Meroitic funerary art. For example, pigments - mainly blue in color- have been preserved on a stele found lying on its side. This is rare for objects of this kind, which typically are subjected to the vagaries of time. Another exceptional find: a chapel lintel representing Maat, the Egyptian goddess of order, equity, and peace. This is the first extant representation of this goddess depicting her with African characteristics. During the last excavation campaign in late 2017, the researchers discovered a stele in the name of a Lady Maliwarase. The stele sets out her kinship with the notables of Nubia (in the north of the kingdom of Meroe): she was the sister of two grand priests of Amon, and one of her sons held the position of governor of Faras, a large city bordering the second cataract of the Nile. The archeologists have also unearthed a lintel inscribed with four lines of text describing the owner of the sepulcher, another great lady, Adatalabe. She hailed from an illustrious lineage that included a royal prince, a member of the reigning family of Meroe. These two steles written for high-ranking women are not isolated examples in Sedeinga. In Meroitic society, it was indeed women who embodied the prestige of a family and passed on its heritage.

Notes

1 The kingdoms of Napata and Meroe formed one and the same civilization, known as the "Kush kingdom" by their ancient Egyptian neighbors.

2 The director of the mission, Claude Rilly, is a CNRS researcher at the Langage, Langues et Cultures d'Afrique Noire laboratory (CNRS/Inalco). He is co-leading this mission with Vincent Francigny, director of the SFDAS (MEAE). This research has been funded by the excavation commission of the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs (MEAE) and the Orient et Mèditerranée - Textes-Archéologie-Histoire laboratory (CNRS/Sorbonne Université/Université Panthéon-Sorbonne/EPHE/Collège de France). The campaign carried out between November, 14 and December 19, 2017, the last to date, was awarded the Fondation Jean et Marie-Thérèse Leclant prize.

3 Excavation work on the site began in 1963 and recommenced in 2009. It will continue until 2020 and is divided into three four-year plans, the last of which began in November 2017.

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/winter-2018/article/archaeologists-unearth-tombs-in-ancient-nubia

|

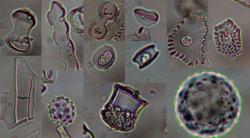

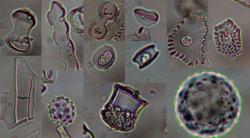

Microscopic plant remains,

called phytoliths, from

grasses, sedges, palms,

forbs, and trees that lived

near Lake Malawi in East

Africa about 74,000 years ago. Chad L. Yost,

University of Arizona Department of

Geosciences

|

No volcanic winter in East Africa from ancient Toba eruption

6 February 2018