At an archaeological site in Ethiopia, researchers are uncovering the oldest Christian basilica in sub-Saharan Africa. (Ioana Dumitru)

|

Church Unearthed in Ethiopia Rewrites the History of Christianity in Africa

10 December 2019

In the dusty highlands of northern Ethiopia, a team of archaeologists recently uncovered the oldest known Christian church in sub-Saharan Africa, a find that sheds new light on one of the Old World's most enigmatic kingdoms - and its surprisingly early conversion to Christianity.

An international assemblage of scientists discovered the church 30 miles northeast of Aksum, the capital of the Aksumite kingdom, a trading empire that emerged in the first century A.D. and would go on to dominate much of eastern Africa and western Arabia. Through radiocarbon dating artifacts uncovered at the church, the researchers concluded that the structure was built in the fourth century A.D., about the same time when Roman Emperor Constantine I legalized Christianty in 313 CE and then converted on his deathbed in 337 CE. The team detailed their findings in a paper published today in Antiquity.

The discovery of the church and its contents confirm Ethiopian tradition that Christianity arrived at an early date in an area nearly 3,000 miles from Rome. The find suggests that the new religion spread quickly through long-distance trading networks that linked the Mediterranean via the Red Sea with Africa and South Asia, shedding fresh light on a significant era about which historians know little.

"The empire of Aksum was one of the world's most influential ancient civilizations, but it remains one of the least widely known," says Michael Harrower of Johns Hopkins University, the archaeologist leading the team. Helina Woldekiros, an archaeologist at St. Louis' Washington University who was part of the team, adds that Aksum served as a "nexus point" linking the Roman Empire and, later, the Byzantine Empire with distant lands to the south. That trade, by camel, donkey and boat, channeled silver, olive oil and wine from the Mediterranean to cities along the Indian Ocean, which in turn brought back exported iron, glass beads and fruits.

The kingdom began its decline in the eighth and ninth centuries, eventually contracting to control only the Ethiopian highlands. Yet it remained defiantly Christian even as Islam spread across the region. At first, relations between the two religions were largely peaceful but grew more fraught over time. In the 16th century, the kingdom came under attack from Somali and then Ottoman armies, but ultimately retained control of its strategic highlands. Today, nearly half of all Ethiopians are members of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

For early Christians, the risk of persecution from the Romans sometimes ran high, forcing them to practice their beliefs in private, posing a challenge for those scholars who study this era. Christianity had reached Egypt by the third century A.D., but it was not until Constantine's legalization of Christian observance that the church expanded widely across Europe and the Near East. With news of the Aksumite excavation, researchers can now feel more confident in dating the arrival of Christianity to Ethiopia to the same time frame.

"[This find] is to my knowledge the earliest physical evidence for a church in Ethiopia, [as well as all of sub-Saharan Africa,]" says Aaron Butts, a professor of Semitic and Egyptian languages at Catholic University in Washington, D.C., who was not involved with the excavation.

Harrower's team conducted their work between 2011 and 2016 at an ancient settlement called Beta Samati, which means "house of audience" in the local Tigrinya language. The location, close to the modern-day border with Eritrea and 70 miles to the southwest of the Red Sea, appealed to the archaeologists in part because it was also home to temples built in a southern Arabian style dating back many centuries before the rise of Aksum, a clear sign of ancient ties to the Arabian Peninsula. The temples reflect the influence of Sabaeans, who dominated the lucrative incense trade and whose power reached across the Red Sea in that era.

The excavators' biggest discovery was a massive building 60 feet long and 40 feet wide resembling the ancient Roman style of a basilica. Developed by the Romans for administrative purposes, the basilica was adopted by Christians at the time of Constantine for their places of worship. Within and near the Aksumite ruins, the archaeologists also found a diverse array of goods, from a delicate gold and carnelian ring with the image of a bull's head to nearly 50 cattle figurines-clearly evidence of pre-Christian beliefs.

They also uncovered a stone pendant carved with a cross and incised with the ancient Ethiopic word "venerable," as well as incense burners. Near the eastern basilica wall, the team came across an inscription asking "for Christ [to be] favorable to us."

In the research paper, Harrower said that this unusual collection of artifacts "suggests a mixing of pagan and early Christian traditions."

According to Ethiopian tradition, Christianity first came to the Aksum Empire in the fourth century A.D. when a Greek-speaking missionary named Frumentius converted King Ezana. Butts, however, doubts the historical reliability of this account, and scholars have disagreed over when and how the new religion reached distant Ethiopia.

"This is what makes the discovery of this basilica so important," he adds. "It is reliable evidence for a Christian presence slightly northeast of Aksum at a very early date."

While the story of Frumentius may be apocryphal, other finds at the site underline how the spread of Christianity was intertwined with the machinations of commerce. Stamp seals and tokens used for economic transactions uncovered by the archaeologists point to the cosmopolitan nature of the settlement. A glass bead from the eastern Mediterranean and large amounts of pottery from Aqaba, in today's Jordan, attest to long-distance trading. Woldekiros added that the discoveries show that "long-distance trade routes played a significant role in the introduction of Christianity in Ethiopia."

She and other scholars want to understand how these routes developed and their impacts on regional societies. "The Aksumite kingdom was an important center of the trading network of the ancient world," says Alemseged Beldados, an archaeologist at Addis Ababa University who was not part of the study. "These findings give us good insight ... into its architecture, trade, civic and legal administration."

"Politics and religion are important factors in shaping human histories, but are difficult to examine archaeologically," says Harrower. The discoveries at Beta Samati provide a welcome glimpse into the rise of Africa's first Christian kingdom - and, he hopes, will spark a new round of Aksum-related excavations.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/church-unearthed-ethiopia-rewrites-history-christianity-africa-180973740/

|

|

|

Ostrich eggshell beads reveal 10,000 years of cultural interaction across Africa

27 November 2019

Ostrich eggshell beads are some of the oldest ornaments made by humankind, and they can be found dating back at least 50,000 years in Africa. Previous research in southern Africa has shown that the beads increase in size about 2,000 years ago, when herding populations first enter the region. In the current study, researchers Jennifer Miller and Elizabeth Sawchuk investigate this idea using increased data and evaluate the hypothesis in a new region where it has never before been tested.

Review of old ideas, analysis of old collections

To conduct their study, the researchers recorded the diameters of 1,200 ostrich eggshell beads unearthed from 30 sites in Africa dating to the last 10,000 years. Many of these bead measurements were taken from decades-old unstudied collections, and so are being reported here for the first time. This new data increases the published bead diameter measurements from less than 100 to over 1,000, and reveals new trends that oppose longstanding beliefs.

The ostrich eggshell beads reflect different responses to the introduction of herding between eastern and southern Africa. In southern Africa, new bead styles appear alongside signs of herding, but do not replace the existing forager bead traditions. On the other hand, beads from the eastern Africa sites showed no change in style with the introduction of herding. Although eastern African bead sizes are consistently larger than those from southern Africa, the larger southern African herder beads fall within the eastern African forager size range, hinting at contact between these regions as herding spread. "These beads are symbols that were made by hunter-gatherers from both regions for more than 40,000 years," says lead author Jennifer Miller, "so changes -- or lack thereof -- in these symbols tells us how these communities responded to cultural contact and economic change."

Ostrich eggshell beads tell the story of ancient interaction

The story told by ostrich eggshell beads is more nuanced than previously believed. Contact with outside groups of herders likely introduced new bead styles along with domesticated animals, but the archaeological record suggests the incoming influence did not overwhelm existing local traditions. The existing customs were not replaced with new ones; rather they continued and incorporated some of the new elements.

In eastern Africa, studied here for the first time, there was no apparent change in bead style with the arrival of herding groups from the north. This may be because local foragers adopted herding while retaining their bead-making traditions, because migrant herders possessed similar traditions prior to contact, and/or because incoming herders adopted local styles. "In the modern world, migration, cultural contact, and economic change often create tension," says Sawchuk, "ancient peoples experienced these situations too, and the patterns in cultural objects like ostrich eggshell beads give us a chance to study how they navigated these experiences."

The researchers hope that this work inspires a renewed interest into ostrich eggshell beads, and recommend that future studies present individual bead diameters rather than a single average of many. Future research should also investigate questions related to manufacture, chemical identification, and the effects of taphonomic processes and wear on bead diameter. "This study shows that examining old collections can generate important findings without new excavation," says Miller, "and we hope that future studies will take advantage of the wealth of artifacts that have been excavated but not yet studied."

Source: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/11/191127161512.htm

|

|

|

Descendants of early Europeans and Africans in US carry Native American genetic legacy

September 19, 2019

Profiles of Native American DNA in modern populations show patterns of migration across the US

Many people in the U.S. do not belong to Native American communities but still carry bits of Native American DNA, inherited from European and African ancestors who had children with indigenous individuals during colonization and settlement. In a new study published 19th September in PLOS Genetics, Andrew Conley of the Georgia Institute of Technology and colleagues investigate this genetic legacy and what it can tell us about how non-natives migrated across the U.S.

When Europeans colonized North America, infectious diseases and violent conflict greatly reduced the numbers of Native Americans living on the continent. Their DNA lives on, however, not only in recognized Native American tribes, but also in the descendants of Europeans and enslaved Africans that settled within the country. To better understand this genetic reservoir, researchers analyzed patterns of Native American ancestry from genomic data collected from descendants of African slaves, and Spanish and Western European settlers.

The analysis showed that African descendants had low levels of Native American ancestry, consistent with the two groups mixing in the Antebellum South, followed by African American dispersal in the Great Migration. European descendants had the lowest amount of Native American ancestry, and showed a historical pattern of continual but infrequent mixing between local Native American groups and European settlers as they moved westward. Spanish descendants had the highest and most variable amounts of Native American ancestry, and their profiles showed regional patterns reflecting the different waves of Spanish-descended immigrants that moved into the country. Native American DNA was sufficient to distinguish between descendants of very early Spanish settlers in the U.S., known as Hispanos or Nuevomexicanos, and descendants of subsequent immigrants arriving from Mexico.

"The presence of Native American genetic ancestry among individuals who do not self-identify as Native American can also be leveraged to broaden genomic medicine and include population groups currently underserved and underrepresented in genomic databases," said author Andrew Conley. "For future studies, we are very interested to use this rich genomic resource to study the distribution of health-related genetic variants in the Native American genomic background."

Overall, the study shows that much of the genetic legacy of the original inhabitants of the area that is now the continental U.S. can be found in the genomes of the descendants of European and African immigrants to the region. By making use of large genomic databases, the new study adds insight into the current discussion of the meaning of Native American identity and its distinction from genetic ancestry.

Source: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/09/190919142344.htm

|

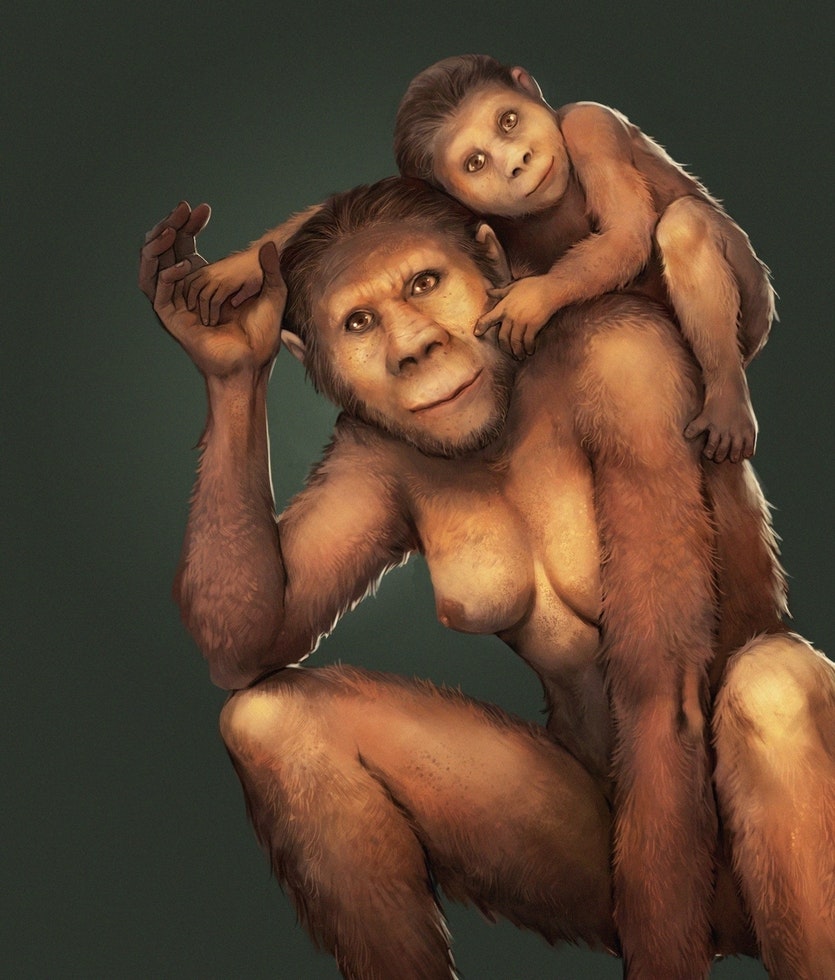

Artist's impression of Australopithecus africanus. Credit: Jose Garcia and Renaud Joannes-Boyau

|

Ancient ancestors cared about their kids

16 July 2019

When times were tough and food was scarce on the savannah, Australopithecus africanus toddlers returned to the boob.

An analysis of fossil teeth, published in the journal Nature, has found that mothers among these extinct human ancestors supplemented their infants' diet with breastmilk long after they had started eating solids.

Lengthy periods of breastfeeding are common in great apes. Gorillas wean at around age four, and chimpanzees stop nursing at about five.

Humans wean comparatively early - usually by age three - but invest heavily in their young in other ways to see them through lengthy childhoods.

Studying breastfeeding in Australopithecus africanus - a hominin that lived more than two million years ago in southern Africa - is part of an effort to trace the origins of this short period of breastfeeding in otherwise late-maturing children.

Renaud Joannes-Boyau, from Australia's Southern Cross University, and colleagues sliced through four teeth from two individuals that were entombed in the Sterkfontein cave site in South Africa between 2.6 and 2.1 million years ago.

Teeth, like trees, have growth rings that provide a record of an animal's life.

By mapping the concentration of barium - an element that is absorbed and incorporated into growing teeth more readily with a diet of milk - the team worked out the breastfeeding patterns of the individuals.

It wasn't what they were expecting.

"The breastfeeding of Australopithecus africanus was unusual," says Joannes-Boyau. "We were expecting something quite long, similar to what we see in modern day great apes, like chimpanzees."

Instead, they found that Australopithecus breastfed exclusively for just six to nine months, at which point solids were introduced. By about a year of age, breastfeeding had tapered off almost entirely.

But annual surges in breastfeeding continued for the next four or five years.

This cyclical pattern of breastfeeding was confirmed by levels of the element strontium. When breastmilk consumption ramped up, as indicated by barium, other sources of food, indicated by strontium, disappeared.

The strategy was probably the product of a harsh environment, with seasonal periods of food scarcity.

"When it's the off season then the mother will supplement a lot of the calorie deficiency with breast milk," says Joannes-Boyau.

The team also looked at the element lithium, which revealed that the hominins were briefly consuming a particular food - perhaps a less desirable fall-back food consumed in the off-season - right before the annual peak in breastfeeding.

The annual cycling of breastmilk consumption is not unlike that seen in orangutans.

Joannes-Boyau believes that instead of moving from place to place to ensure year-round food, Australopithecus africanus bet on a strategy of sticking it out in tough conditions with fewer predators.

"Perhaps this environment that is not offering much food and so on forces them to invest a little bit more in each offspring instead of having a lot of kids," he adds.

The heavy investment in children more than two million years ago was an early sign of things to come, he says.

The team are analysing teeth from other extinct members of the human family tree to flesh out the picture of how our own childhoods were shaped by evolution.

Source: https://cosmosmagazine.com/palaeontology/ancient-ancestors-cared-about-their-kids

|

legende image

|

Ancient Humans Dietary Habits Reflected In Bonobo Aquatic Greens Diet

3 July 2019

Bonobos have been spotted doing something interesting in the Congo basin. They are scouring the swamp in search of aquatic herbs that are packed with iodine, a nutrient that is very important for advancing the growth of higher cognitive abilities. That could help scientists understand the nutritional needs and practices of ancient humans. The Bonobo consumption of food rich in iodine is the first-ever recorded by a species other than humans.

"Our results have implications for our understanding of the immigration of prehistoric human populations into the Congo basin," Dr. Gottfried Hohmann, the lead author of the study comments.

"Bonobos as a species can be expected to have similar iodine requirements to humans, so our study offers - for the first time - a possible answer on how pre-industrial human migrants may have survived in the Congo basin without artificial supplementation of iodine," the researcher added.

Scientists working on the study have been observing the behavior of separate bonobo communities in the Congo region. The consumption of iodine-rich plants by specific individuals was factored into their observations, something that surprised researchers, due to the will of the primates to actively seek out the particular plants. It was also believed that the region did not have any iodine-rich food sources.

According to Dr. Hohmann, evolutionary theories suggest that early humans have been able to evolve by living in coastal areas. There they could find favorable foods that augmented cerebral functions. Their study suggests that early humans may have triggered their cerebral development by eating some of the same food the Bonobos are consuming now.

Bonobos are not the only species to consume the plants. After this observation, it was reported that some gorillas and chimpanzees also seek out iodine-rich aquatic greens. That proves to be an exciting development, as different primate species are seeking out and finding these essential plants in areas that were believed to be scarce in iodine.

Source: https://greatlakesledger.com/2019/07/03/ancient-humans-dietary-habits-reflected-in-bonobo-aquatic-greens-diet/

|

|

Prehistoric humans invented stone tools multiple times, study finds

3 June 2019

Prehistoric humans invented tools on multiple occasions, according to researchers who have found a collection of 327 stone weapons carved more than 2.58 million years ago.

This is the first evidence of ancient hominids sharpening stones to create specific tools, according to new research led by Arizona State University and George Washington University.

The collection of "Oldowan" tools - which are created by chipping off bits of stone - were found in the Afar region of north-eastern Ethiopia. They were probably made so our ancestors could carve up meat.

Before this discovery, the oldest example of an Oldowan tool was found in Gona in Ethiopia and was believed to be 2.56 million years old. It was widely believed this technology was invented once and then spread across the continent.

However, this latest study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, proves that theory wrong. Oldowan tools are now believed to have been invented many times by several hominid groups before becoming an essential human survival tool.

Kaye Reed research associate with Arizona State University's Institute of Human Origins told The Independent: 'This is the first time we see people chipping off bits of stone to make tools with an end in mind. They only took two or three flakes off, and some you can tell weren't taken off quite right.

'The latest tools seem slightly different in the way they're made from other examples.'

The tools were found near the oldest fossil attributed to the genus Homo, which is at an excavation site known as Bokol Dora 1 or BD 1 in Ethiopia. For five years researchers had been trying to find if there was a connection between the origins of our genus and the creation of systematic stone tool manufacture.

The breakthrough came when Arizona State University geologist Christopher Campisano saw sharp-edged stone tools sticking out of the sediments on a steep, eroded slope. It was here they went on to find hundreds of small pieces of chipped stones.

"These tools were dropped by early humans at the edge of a water source and then quickly buried. The site then stayed that way for millions of years,” said geoarchaeologist Vera Aldeias from the University of Algarve in Portugal.

Our ancestors were making and using tools for one million years before this latest find. Old hammering or "percussive" stone tools described as "Lomekwian" tools were first found in Kenya 3.3 million years ago.

Like monkeys and chimpanzees, these early hominids were using tools to hammer and bash food items like nuts and shellfish. However, something changed by 2.6 million years ago and our ancestors became more accurate and skilled at striking the edge of stones to make tools.

The BD 1 artefacts capture this shift.

"We expected to see some indication of an evolution from the Lomekwian to these earliest Oldowan tools," said Will Archer of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig and the University of Cape Town.

"Yet when we looked closely at the patterns, there was very little connection to what is known from older archaeological sites or to the tools modern primates are making," he said.

This change coincided with a change in our ancestor’s teeth. As our ancestors began to process food prior to eating using stone tools, we start to see a reduction in the size of their teeth.

David Braun, an archaeologist with George Washington University and the lead author on the paper said; "Given that primate species throughout the world routinely use stone hammers to forage for new resources, it seems very possible that throughout Africa many different human ancestors found new ways of using stone artefacts to extract resources from their environment.

"If our hypothesis is correct then we would expect to find some type of continuity in artefact form after 2.6 million years ago, but not prior to this time period. We need to find more sites."

Dr Reed said: "Our team is going back to the field early next year and we will do some more excavations of other localities and we'll keep looking for more hominids that made the tool."

Source: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/tools-invention-prehistoric-human-oldowan-stone-weapons-arizona-state-university-a8942261.html

|

Inheriting herding. Ancient DNA indicates that early African herders started mating with hunter-gatherers more than 5,000 years ago. Here, modern herders in Tanzania watch over their goats. Katherine Grillo

|

Africa's first herders spread pastoralism by mating with foragers

30 May 2019

Ancient sheep, goat and cattle herders made Africa their home by hooking up with the continent's native hunter-gatherers, a study suggests.

DNA analysis shows that African herders and foragers mated with each other in two phases, says a team led by archaeologist Mary Prendergast of Saint Louis University in Madrid. After entering northeastern Africa from the Middle East around 8,000 years ago, herders swapped DNA with native foragers between roughly 6,000 and 5,000 years ago. Herders possessing some forager heritage then trekked about halfway down the continent and mated with eastern African foragers around 4,000 years ago, the scientists report online May 30 in Science.

Present-day herders, such as the Dinka in South Sudan, still live in eastern Africa. But how pastoralism spread into the region has been a mystery. In particular, it has been difficult to tell whether ancient African hunter-gatherers mated with early herders or simply adopted their livestock practices. The new study supports an emerging view from ancient DNA studies that human cultural evolution has often featured mating across groups with different traditions and lifestyles.

Prendergast and her colleagues analyzed tooth and bone DNA from 41 individuals whose remains were previously found at herding and foraging sites in Kenya and Tanzania with ages ranging between about 4,000 and 100 years old. Those genetic data were compared with DNA previously collected by other researchers from present-day African herders as well as DNA extracted from roughly 6,000-year-old remains of Middle Eastern farmers - the closest population to northeastern Africa at that time with available genetic data - and bones of African foragers, including one who lived in East Africa as early as 4,500 years ago (SN: 11/14/15, p. 12).

Early African herders inherited about 20 percent of their DNA from foragers, mostly via mating that occurred before 5,000 years ago, the scientists say. Herders then spread rapidly throughout eastern Africa after 3,300 years ago, mating little with foragers along the way.

M.E. Prendergast et al. Ancient DNA reveals a multistep spread of the first herders into sub-Saharan Africa. Science. Published online May 30, 2019. doi:10.1126/science.aaw6275.

Source: https://www.sciencenews.org/article/africa-ancient-herders-spread-pastoralism-mating-foragers

|

The Klasies River cave in the southern Cape of South Africa

|

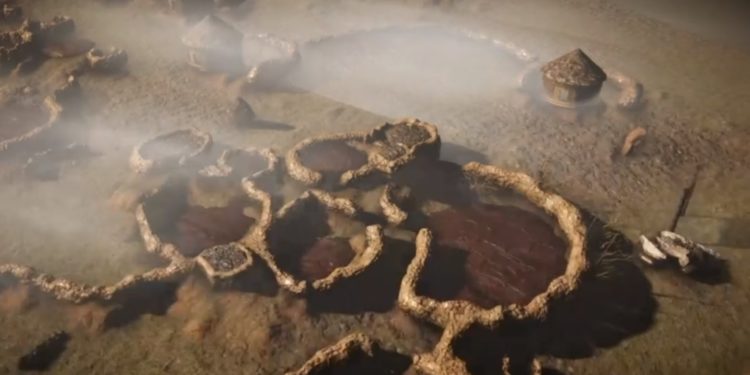

Earliest evidence of the cooking and eating of starch

17 May 2019

Early human beings who lived around 120,000 years ago in South Africa were 'ecological geniuses' who were able to exploit their environment intelligently for suitable food and medicines.

New discoveries made at the Klasies River Cave in South Africa's southern Cape, where charred food remains from hearths were found, provide the first archaeological evidence that anatomically modern humans were roasting and eating plant starches, such as those from tubers and rhizomes, as early as 120,000 years ago.

The new research by an international team of archaeologists, published in the Journal of Human Evolution, provides archaeological evidence that has previously been lacking to support the hypothesis that the duplication of the starch digestion genes is an adaptive response to an increased starch diet.

"This is very exciting. The genetic and biological evidence previously suggested that early humans would have been eating starches, but this research had not been done before," says Lead author Cynthia Larbey of the Department of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge. The work is part of a systemic multidisciplinary investigation into the role that plants and fire played in the lives of Middle Stone Age communities.

The interdisciplinary team searched for and analysed undisturbed hearths at the Klasies River archaeological site.

"Our results showed that these small ashy hearths were used for cooking food and starchy roots and tubers were clearly part of their diet, from the earliest levels at around 120,000 years ago through to 65,000 years ago," says Larbey. "Despite changes in hunting strategies and stone tool technologies, they were still cooking roots and tubers."

Professor Sarah Wurz from the School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa (Wits University) and principal investigator of the site says the research shows that "early human beings followed a balanced diet and that they were ecological geniuses, able to exploit their environments intelligently for suitable foods and perhaps medicines".

By combining cooked roots and tubers as a staple with protein and fats from shellfish, fish, small and large fauna, these communities were able to optimally adapt to their environment, indicating great ecological intelligence as early as 120 000 years ago.

"Starch diet isn't something that happens when we started farming, but rather, is as old as humans themselves," says Larbey. Farming in Africa only started in the last 10 000 years of human existence.

Humans living in South Africa 120 000 years ago formed and lived in small bands.

"Evidence from Klasies River, where several human skull fragments and two maxillary fragments dating 120 000 years ago occur, show that humans living in that time period looked like modern humans of today. However, they were somewhat more robust," says Wurz.

Klasies River is a very famous early human occupation site on the Cape coast of South Africa excavated by Wurz, who, along with Susan Mentzer of the Senckenberg Institute and Eberhard Karls Universit?t Tübingen, investigated the small (c. 30cm in diameter) hearths.

###

The research to look for the plant materials in the hearths was inspired by Prof Hilary Deacon, who passed on the Directorship of the Klasies River site on to Wurz. Deacon has done groundbreaking work at the site and in the 1990's pointed out that there would be plant material in and around the hearths. However, at the time, the micro methods were not available to test this hypothesis.

Source: https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2019-05/uotw-eeo051719.php

|

|

Huge growth in use of quartz for tools shows sophistication of ancient communities

10 May 2019

A growth in the use of crystal quartz to make tools thousands of years ago shows the sophistication of ancient communities, according to new research.

The mineral was chosen because of its powerful symbolism, even though it involved painstaking work and other materials that would have been easier to use were available to prehistoric toolmakers, archaeologists argue.

Archaeologists have found there was a sudden spike in the number of tiny hand-made tools of less than 1cm made of crystal quartz in southern Africa around 14,000 years ago.

People could have used chert, which was more durable and found locally, but they may have chosen crystal quartz because it has several unique properties including as a source of light when it is struck and as a source of sharp cutting edges. Communities may have engaged with crystal quartz because they saw material as "alive" and believed they were able to harness the power from the mineral to see into the future.

The technique of constructing tiny crystal quartz tools would have taken specific sets of skills to master. Crystal quartz was also used in other parts of the world for tools at this time, when other raw materials were available. Crystal quartz is brittle and can fracture, but can give an exceptionally sharp and precise cutting edge.

Archaeologists examined two sites, in Sehonghong and Ntloana Tšoana, in Lesotho which are approximately 100 km apart from each other and in very different environments. Although communities used other raw materials for tool production, after around 14,000 years ago they both increasingly started to use crystal quartz. In some layers excavated more than 75 per cent of tools were made of the mineral, particularly those which hold remains from 18 thousand years ago at Sehonghong. This suggests that widely dispersed hunter-gatherer groups were connected and engaged with one another.

"We show that although crystal quartz was never the dominant raw material for tool production at either Sehonghong or Ntloana Tsoana, the mineral does show increased frequencies after 14,000 years ago," says first author Justin Pargeter, from Emory University. "This pattern is shared between the two sites, separated by 100 kilometers and in very different environments, which suggests that widely dispersed hunter-gatherer groups were connected and engaged with one another."

Dr. Jamie Hampson, from the University of Exeter, who is co-author of the paper, said: "Quartz is abundant in the region, but from a functional point of view it is not the best material for making small tools. It takes more energy and time to use this material. If it flakes well, it can provide an extremely sharp cutting tool. But most of the time it just shatters.

"We found stone tools became smaller and smaller, there was a spike in their use, and increasingly they were made of crystal quartz instead of chert, which would have been a more readily available rock. We can't say for sure why crystal quartz was used, but it may have been chosen for its unique symbolic qualities. This shows communities were more sophisticated and thoughtful than they were previously given credit for."

Evidence from ethnographic texts and also from rock paintings suggests ancient communities at the time – in this region and elsewhere around the world—entered a hallucinogenic state. The luminescence caused by the sparks when crystal quartz was hit may have been part of their rituals performed in order to enter an altered state of consciousness and access the spirit world.

Dr. Hampson has been examining evidence from cave paintings and engravings for 20 years, showing how they depict and embody these rituals. In some places people put pieces of quartz into gaps and cracks in the rock faces, seen by many indigenous communities as the barrier between their world and the spiritual world.

Source: https://phys.org/news/2019-05-huge-growth-quartz-tools-sophistication.html

|

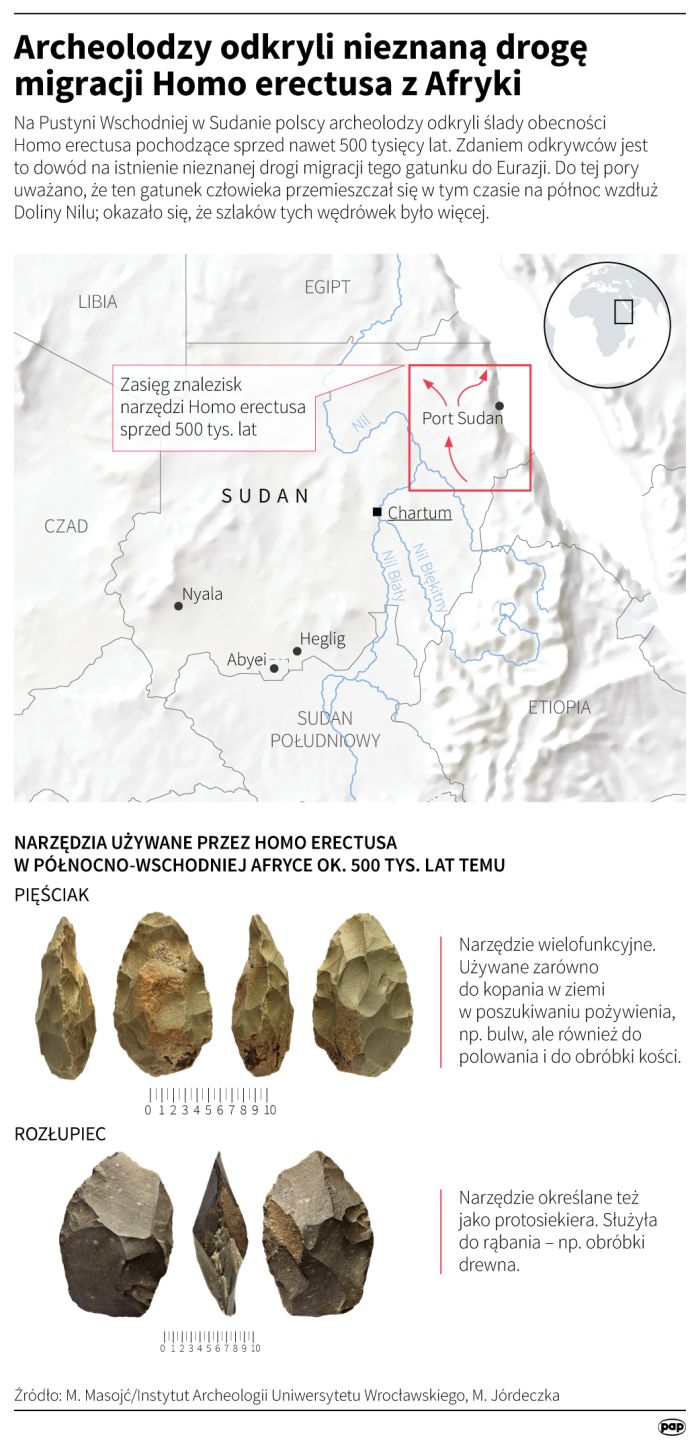

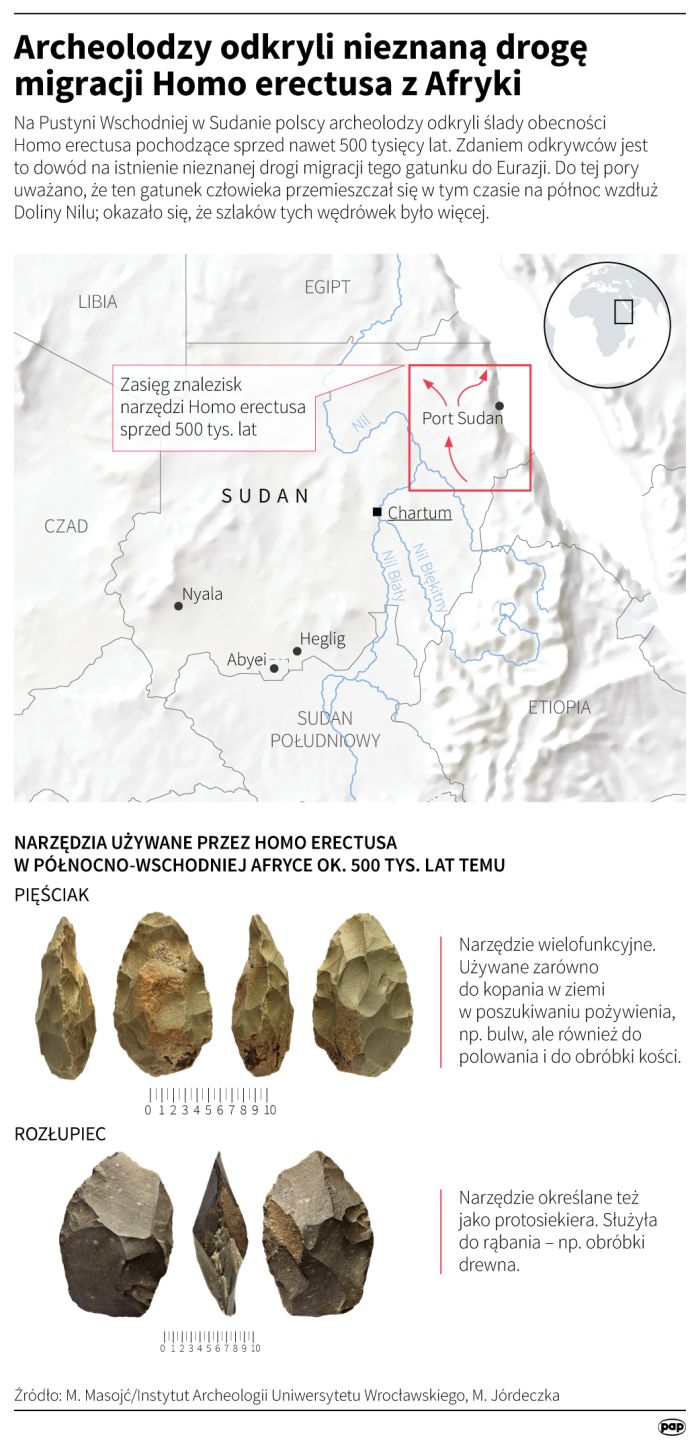

Homo erectus migrations from Africa. Source: PAP Infographics

|

Polish archaeologists have discovered an unknown migration route of homo erectus from Africa

8 May 2019

In the Eastern Desert in Sudan, Polish archaeologists have found 500,000 years old traces of the presence of Homo erectus. According to the discoverers, it is a proof of existence of an unknown migration route of this species beyond the continent.

The African variety of Homo erectus (upright man) - the ancestor of modern man (Homo sapiens) - appeared in Africa about 1.8 million years ago, from where it quickly migrated to Eurasia. These migrations took place in stages.

The eastern Africa is considered the cradle of humanity. The oldest traces of human activity in the form of stone tools have been discovered along the Great Rift Valley, which stretches from Mozambique through Tanzania to the coast of the Red Sea in the region of Eritrea and Ethiopia. In terms of research on the oldest traces of man, the area farther to the north of Africa - the Eastern Desert in Sudan - is somewhat forgotten. Polish archaeologists decided to focus on this area. The project funded by the National Science Centre involves scientists from Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Germany and the US.

Up to now, the prevailing views were that H. erectus moved north mainly along the Nile Valley.

The researcher adds that although today the study area is a flat and inhospitable desert, hundreds of thousands of years ago there were periods of a much more humid climate. There was vegetation and rivers - their dried beds indicate the course towards the north-east, towards the Red Sea.

Discoveries in the Eastern Desert also confirm the long coexistence of Homo erectus with Homo sapiens in Africa: it is a period of at least 100,000. years, between 300,000 and 200,000 years ago. Both species lived there simultaneously, although one gave birth to the other.

The discovery of over half a million years old stone tools was made accidentally in recent years. "There was a gold rush in the eastern part of Sudan, in the Eastern Desert, as in many places in the Sahara - people looking for this precious metal in makeshift, open-cast mines. By uncovering successive layers, miners came across tools from several hundred thousand years ago" - says Prof. Masojc.

Alerted by reports of unusual finds, archaeologists set out into the field. "We work in the mines after miners have already left them, so there is no conflict of interest" - the scientist adds.

So far, researchers have found almost 200 places where Palaeolithic stone products have been preserved. Some of them are located in mines, about 350 km north of Khartoum. The archaeologists find various tools used both by Homo erectus - hand axes and pebble tools, and by Homo sapiens - for example blades. Ancient people used mainly quartzite and volcanic rocks. The age of the tools ranges from more than half a million to 60,000 years. "It would not be possible to find these traces without mining operations" - the archaeologist says.

The first results of the project have just been published in the Journal of Human Evolution (DOI: 10.1016 / j.jhevol.2019.01.014). Additional information about the project can be found at: http://sudan.archeo.uni.wroc.pl/

Source: http://scienceinpoland.pap.pl/en/news/news%2C76941%2Cpolish-archaeologists-have-discovered-unknown-migration-route-homo-erectus-africa

|

Samples being collected from mummified remains at El Museo Canario in the Canary Islands.

Credit: Desenfoque Producciones

|

DNA Clues to an Ancient Canary Islands Voyage

21 March 2019

Today the Canary Islands are a tourist hub, a volcanic archipelago with palm trees and azure beaches, located off the coast of Morocco and governed by Spain. But the history of this paradise is marred by the brutal conquest, enslavement and treatment of its indigenous people by European colonizers beginning around the 15th century.

Although scientists know a fair bit about the fate of the islands' original inhabitants, much is unknown about their origins. Some scholars have debated whether the indigenous people sailed to the islands themselves more than a thousand years ago or were stranded there by ancient Mediterranean mariners.

Increasingly, the evidence points to an intentional journey. Ancient DNA from skeletal remains found across the islands now suggests that the islands' earliest pioneers were North Africans who may have arrived around 100 C.E. or earlier, and settled on every island by at least 1000 C.E. The finding supports previous archaeological, anthropological and genetic studies indicating that the island's first inhabitants were Berbers from North Africa, a group that today lives in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya and parts of the Sahara.

"This is the first ancient DNA study that includes archaeological remains from all the seven Canary Islands," said Rosa Fregel, a population geneticist at the Universidad de La Laguna in Spain. Her team's results, which were published Wednesday in the journal PLOS One, also undercut the idea that the islands' early indigenous inhabitants were not explorers in their own right.

The debate over how, when and why the Canary Islands were first populated arose in part from records made by Europeans in the 1400s, which claimed the native Canarians had no navigational skills. The texts have led scholars to wonder how the indigenous people, who consist of several different tribes such as the Guanches and Bimbapes, reached the islands. Were they brought by Romans or Carthaginians, or did they have the means and ability to sail there themselves?

"The case of the Canary Islands is of particular interest because the indigenous culture and language was lost after the European colonization, complicating our ability to know more about the past,' said Laura Botigué, an expert in North African genetics at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, who was not involved in the study.

To investigate the early peopling of the Canary Islands before Europeans arrived and introduced the slave trade, Dr. Fregel and her colleagues collected nearly 50 mitochondrial genomes from remains at 25 sites. Mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited from one's mother who inherited it from their mother and so on, offer population geneticists clues to help decipher ancient human migrations. Most of the sites were radiocarbon dated between approximately 150 and 1400 C.E., although a couple of them came after post-conquest periods.

"In the Canary Islands indigenous people, we find typical North African lineages, but also some other lineages with a Mediterranean distribution, and also some lineages that are of sub-Saharan African origin," Dr. Fregel said. That fits with the archaeological and genetic history of North Africa, she said: Previous studies have shown that by the time the Canary Islands were inhabited, Berbers from North Africa had already mixed with Mediterranean and sub-Saharan African groups.

In their analysis, the team found that some of the islands did not have much genetic diversity, whereas others had a great deal, indicating that these ancient populations may have been large. The researchers found lineages that were known only from the central part of North Africa, as well as more common lineages from other parts of North Africa, Europe and the Near East. The team also found four new lineages exclusive to Gran Canaria and two eastern islands.

"This is interesting," said Dr. Fregel. "It could mean that the colonization happened in at least two phases, with the second migration wave affecting only the islands closer to the African continent."

Dr. Fregel said that although her findings don't show how ancient people reached the Canaries, they do provide further evidence that the movement was a large one, made by people who had the resources to survive on the islands.

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/21/science/canary-islands-indigenous-dna.html

|

|

Disorder left ancient human relative with teeth pocked like golf balls

7 March 2019

Add this to your list of nightmare jobs: prehistoric dentist. Had the profession existed 1.8 million years ago, it would have encountered an ancient human relative with a disconcertingly common dental disorder: weakened, pockmarked teeth resembling the surface of a golf ball.

The patient in question is Paranthropus robustus, a massive-jawed, thick-molared creature that looked a bit like a gorilla and feasted on tropical grasses, hard seeds and nuts, and fibrous fruits in southern Africa. Scientists have long suspected P. robustus's tough, gritty diet contributed to the overall poor condition of the species's fossil teeth found over the years.

Hoping to learn more, paleontologists compared hundreds of fossilized P. robustus teeth, pictured above, with those of other southern African hominins such as Australopithecus sediba and A. africanus that lived at roughly the same time, as well as with more recent hominins and living apes. The golf ball-like pitting was a common feature of P. robustus teeth, showing up in 47% of baby teeth and 14% of permanent teeth of the species, whereas it occurred only in about 7% and 4%, respectively, of the baby and permanent teeth of the other ancient hominins combined. These pits in the teeth enamel would have made them wear down quickly and break easily.

However, these defects probably didn't come from P. robustus's diet. The condition closely resembles a somewhat rare modern genetic disorder called amelogenesis imperfecta that affects about one in 1000 people worldwide, the researchers report this week in the Journal of Human Evolution. The disorder causes a breakdown in enamel-producing cells, leading to scattered pits and grooves in the teeth.

How did P. robustus develop this condition? In modern humans, the genes responsible also contribute to thick, dense enamel. It's possible, the researchers suggest, that the defect was a side effect of evolving thicker, denser teeth to cope with the species's rough diet.

Source: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/03/disorder-left-ancient-human-relative-teeth-pocked-golf-balls

|

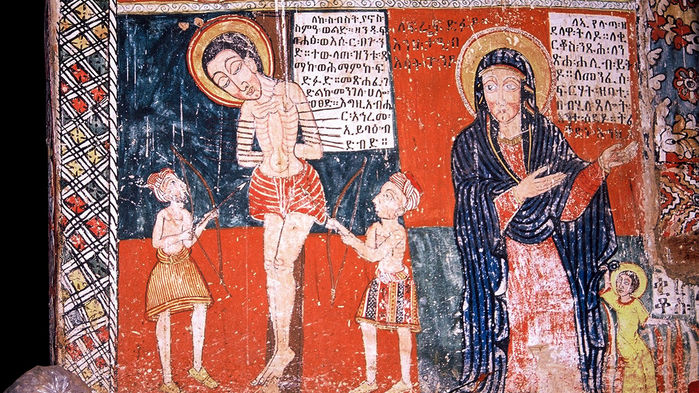

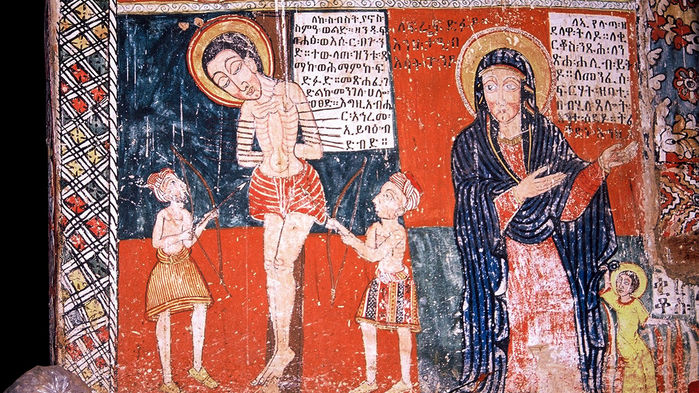

Medieval Ethiopians adopted European plague saints, including St. Sebastian, shown here in

a 17th century mural from a church in Ethiopia. Claire Bosc-Tiesse and Anaïs

Wion

|

The Black Death may have transformed medieval societies in sub-Saharan Africa

6 March 2019

In the 14th century, the Black Death swept across Europe, Asia, and North Africa, killing up to 50% of the population in some cities. But archaeologists and historians have assumed that the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis, carried by fleas infesting rodents, didn't make it across the Sahara Desert. Medieval sub-Saharan Africa's few written records make no mention of plague, and the region lacks mass graves resembling the "plague pits" of Europe. Nor did European explorers of the 15th and 16th centuries record any sign of the disease, even though outbreaks continued to beset Europe.

Now, some researchers point to new evidence from archaeology, history, and genetics to argue that the Black Death likely did sow devastation in medieval sub-Saharan Africa. "It's entirely possible that [plague] would have headed south," says Anne Stone, an anthropological geneticist who studies ancient pathogens at Arizona State University (ASU) in Tempe. If proved, the presence of plague would put renewed attention on the medieval trade routes that linked sub-Saharan Africa to other continents. But Stone and others caution that the evidence so far is circumstantial; researchers need ancient DNA from Africa to clinch their case. The new finds, to be presented this week at a conference at the University of Paris, may spur more scientists to search for it.

Plague is endemic in parts of Africa now; most historians have assumed it arrived in the 19th century from India or China. But Gérard Chouin, an archaeologist and historian at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, and a team leader in the French National Research Agency's GLOBAFRICA research program, first started to wonder whether plague had a longer history in sub-Saharan Africa while excavating the site of Akrokrowa in Ghana. Founded around 700 C.E., Akrokrowa was a farming community surrounded by an elliptical ditch and high earthen banks, one of dozens of similar "earthwork" settlements in southern Ghana at the time. But sometime in the late 1300s, Akrokrowa and all the other earthwork settlements were abandoned. "There was a deep, structural change in settlement patterns," Chouin says, just as the Black Death ravaged Eurasia and North Africa. With GLOBAFRICA funding, he has since documented a similar 14th century abandonment of Ife, Nigeria, the homeland of the Yoruba people, although that site was later reoccupied.

Events in the 14th century also transformed the site of Kirikongo in Burkina Faso, where Daphne Gallagher and Stephen Dueppen, archaeologists at the University of Oregon in Eugene, recently excavated. Starting around 100 C.E., people there farmed, herded cattle, and worked iron. The settlement steadily grew for more than 1000 years. Then, sometime in the second half of the 14th century, it suddenly shrank by half. There's no evidence of food stress, conflict, or migration. "We don't see it coming," Gallagher says. Stone says the sudden changes at Kirikongo and Akrokrowa resemble those seen in the British Isles during the Justinian Plague in the sixth to the eighth centuries C.E.

New hints are also turning up in historical records. Historians have found previously unknown mentions of epidemics in Ethiopian texts from the 13th to the 15th centuries, including one that killed "such a large number of people that no one was left to bury the dead." It's not clear what the disease was, but historian Marie-Laure Derat of the French National Center for Scientific Research in Paris found that by the 15th century, Ethiopians had adopted two European saints associated with plague, St. Roch and St. Sebastian.

Some genetic evidence supports the idea, too. A 2016 study in Cell Host & Microbe revealed a distinct subgroup of Y. pestis now found only in East and Central Africa is a cousin of one of the strains that devastated Europe in the 14th century. "It's the closest living relative to the Black Death strain," says Monica Green, an ASU historian of plague who analyzed this and other previously published plague phylogenies in the journal Afriques. "We [historians] have no story that fits with this evidence that the genetics is screaming about." She thinks this Black Death relative likely arrived in East Africa in the 15th or 16th centuries - after another, now-extinct Y. pestis strain had already burned through West Africa and perhaps beyond.

"[Green's] analysis is very strong," says Javier Pizarro-Cerda, a microbiologist at the Pasteur Institute in Paris who studies Y. pestis. It's intriguing, agrees Benjamin Adisa Ogunfolakan, an archaeologist and director of the Museum of Natural History at Obafemi Awolowo University in Ife, but the evidence so far isn't strong enough to rewrite centuries of African history.

"The silver bullet I dream of," Chouin says, is ancient Y. pestis DNA from human remains in sub-Saharan Africa. Although the region's heat and humidity quickly degrade DNA, Stone hopes researchers will begin to look for DNA in human teeth, where Y. pestis DNA is most likely to be preserved.

Whatever calamity struck medieval sub-Saharan Africa, its impact was lasting. Akrokrowa was abandoned by about 1365, and Kirikongo was never the same. The settlement stayed small, the ceramics got much simpler, and the culture changed to more closely resemble that of the nearby Mali Empire. "It does seem to be a break," Dueppen says. He hopes more archaeologists will start to focus on the 14th century in Africa, looking for hints of plague - or evidence that rules it out. "This is just the beginning of the story," Dueppen says.

Source: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/03/black-death-may-have-transformed-medieval-societies-sub-saharan-africa

|

Columbus's ship the Santa María runs aground off what is now Haiti on Christmas Day 1492.

Photograph: Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty

|

Spain logs hundreds of shipwrecks that tell story of maritime past

1 March 2019

Weather rather than pirates caused majority of sinkings, says culture ministry team.

The treacherous waters of the Americas had their first taste of Spanish timber on Christmas Day 1492, when Christopher Columbus' flagship, the Santa María, sank off the coast of what is now Haiti.

Over the following four centuries, as Spain's maritime empire swelled, peaked and collapsed, the waves on which it was built devoured hundreds of ships and thousands of people, swallowing gold, silver and emeralds and scattering spices, mercury and cochineal to the currents.

Today, three researchers working for the Spanish culture ministry have finished the initial phase of a project to catalogue the wrecks of the ships that forged and maintained the empire.

Led by an archaeologist, Carlos León, the team has logged 681 shipwrecks off Cuba, Panama, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Bermuda, the Bahamas and the US Atlantic coast.

Its inventory runs from the sinking of the Santa María to July 1898, when the Spanish destroyer Plutón was hit by a US boat off Cuba, heralding the end of the Spanish-American war and the twilight of Spain's imperial age.

After spending five years scouring archives in Seville and Madrid, León, his fellow archaeologist Beatriz Domingo and the naval historian Genoveva Enríquez have put together a list aimed at safeguarding the future and shedding light on the past.

"We had two fundamental objectives," says León. "One was to come up with a tool that can be used for identifying and protecting wreck sites - especially in areas where there's a high concentration of sunken ships."

"The other was to recover a bit of history that's been very much forgotten. The most famous ships have been investigated, but there's a huge number about which we know absolutely nothing. We don't know how they sank, or how deep."

The information gathered would help the team to find out what navigation was like at the time, he said.

The team's research will thrill historians and cartographers, but is unlikely to delight those who harbour romantic notions about doubloons, parrots and Jolly Rogers.

It found that 91.2% of ships were sunk by severe weather - mainly tropical storms and hurricanes - 4.3% ran on to reefs or had other navigational problems, and 1.4% were lost to naval engagements with British, Dutch or US ships. A mere 0.8% were sunk in pirate attacks.

Archaeologists have located the remains of fewer than a quarter of the 681 vessels on the inventory to date.

León, Domingo and Enríquez were surprised to come across 12 areas with particularly high concentrations of wrecks in Panama, the Dominican Republic and the Florida Keys. Instead of the expected two or three wrecks per bay, they discovered as many as 18.

"Some of these areas, like Damas bay in Panama, are very open," says León. "There were huge annual trade festivals there from the 16th century to the mid-17th and that attracted a massive amount of maritime traffic. It's not a very protected area and so when a storm came in, the ships sank."

Or, to put it in more modern terms: "It was like a motorway. It's not very deep there, either. And ships are a bit like aeroplanes. They usually go down on take-off or landing."

Treasure hunters tend to be more interested in ships that came to grief on their way back from the Americas, but León and his colleagues say the ill-fated outward-bound vessels are just as compelling.

"The cargo they carried speaks of a massive amount of trade," says the archaeologist. "But it's not just about products and trade. These ships were also carrying ideas. We were surprised to find a lot of boats loaded with religious objects - relics, decorations and even stones to build churches."

Their findings, however, go beyond cutlasses and crucifixes, and help to explain how Spain succeeded in enriching itself for centuries.

As well as the "tonnes and tonnes" of mercury sent to the new world to be used in extracting gold and silver from the mines that fed the empire, "we found boats that were carrying clothes for slaves". Others carried weapons to be used in putting down local rebellions.

The researchers now plan to transfer the paper inventory to a database that the Spanish government can share with countries with colonial shipwrecks in their waters. León hopes the information his team has gathered will give those countries what they need to safeguard their maritime heritage against unscrupulous treasure hunters who all too often use salvage permits as a cover for more profitable explorations.

"We have to be very careful about the details and positions of some of the ships," he says. "But the ministry works with countries that have ratified the 2001 Unesco convention [on the protection of the underwater cultural heritage], so they should be countries that aren't going to use this information to make deals with treasure-hunting firms."

Anyway, he adds, the big treasure-hunting outfits will not be interested in most of the wrecks on the inventory. "It's true that the big treasure-hunting firms have spent years doing what we've been doing, but only when it comes to the ships that carried huge treasure loads. I don't think we'd be helping them out much, to be honest."

The three researchers are now preparing for another deep dive, into the archives and libraries. The Spanish empire was, after all, a very, very large one. "We've still got many more areas to go," says León. "Next year, I'd like to work on Mexico, Colombia, Puerto Rico and Costa Rica so as to kind of finish up the Caribbean area. After that's it's on to the Pacific."

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2019/mar/01/spain-logs-shipwrecks-maritime-past-weather-pirates

|

Walking tall. A researcher holds an Ardipithecus ramidus ankle bone after

its discovery at an East African site not far from where Ardi, a partial skeleton of the same species, was found previously. S.W. Simpson

|

African hominid fossils show ancient steps toward a two-legged stride

22 February 2019

New cache of Ardipithecus ramidus bones reveals advances in upright walking 4 million years ago.

Fossils unearthed from an Ethiopian site not far from where the famous hominid Ardi's partial skeleton was found suggest that her species was evolving different ways of walking upright more than 4 million years ago.

Scientists have established that Ardi herself could walk upright (SN Online: 4/2/18). But the new fossils demonstrate that other members of Ardipithecus ramidus developed a slightly more efficient upright gait than Ardi's, paleoanthropologist Scott Simpson and colleagues report in the April Journal of Human Evolution. The fossils, excavated in Ethiopia's Gona Project area, are the first from the hominid species since 110 A. ramidus fossils, including Ardi's remains, were found about 100 kilometers to the south (SN: 10/24/09, p. 9).

Gona field surveys and excavations from 1999 through 2013 yielded A. ramidus remains, including 42 lower-body fossils, two jaw fragments and a large number of isolated teeth. Several leg and foot bones, along with a pelvic fragment, a lower back bone and possibly some rib fragments, came from the same individual. The same sediment layers, characterized by previously dated reversals of Earth's magnetic field, contained fossils of extinct pigs, monkeys and other animals known to have lived more than 4 million years ago.

Unlike Ardi, the fossil individual at Gona walked on an ankle that better supported its legs and trunk, says Simpson, of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. And only the Gona hominid could push off its big toe while striding on two legs.

Still, Ardi shares a style of movement with the 4.8-million- to 4.3-million-year-old Gona hominids that is unlike that of any other hominid or living primate, the researchers say. The fossils found at Gona and at Ardi's site suggest grasping, opposable toes, flat feet and other skeletal features that would have made A. ramidus a capable, but not acrobatic, tree climber, probably limited to moving on all fours across low-hanging branches. Ardi's kind was also built for walking slowly over relatively short distances.

Skeletal modifications that improved upright walking at Gona increase the probability that Ar. ramidus evolved into the first known Australopithecus species around 4.2 million years ago (SN: 4/15/06, p. 227), Simpson's team says. Humanlike walking first appeared in Australopithecus, with the best fossil evidence coming from A. afarensis. Lucy's famous, 3.2-million-year-old partial skeleton belongs to that species.

Stepping up - below

Corresponding ankle bones come from a more than 4-million-year-old Ardipithecus ramidus individual at Ethiopia's Gona site (left), a member of the same species dubbed Ardi from a nearby site (middle), and from Lucy, a 3.2-million-year-old representative of Australopithecus afarensis (right). Both the Gona individual and Lucy possessed humanlike ankles.

It's also possible, the researchers say, that Ardi's kind evolved apart from Australopithecus into a line of hominids that fell short of humanlike walking abilities (SN: 5/5/12, p. 18).

"I had a tough time seeing Ardi evolving into Australopithecus, but the Gona fossils make that transition easier to envision," says paleoanthropologist Jeremy DeSilva of Dartmouth College, who did not participate in the new study. In particular, the shape of an Ardipithecus ankle bone from Gona shows that its foot, unlike Ardi's, was positioned directly under the shin bone, as in people today.

The discoveries at Gona strengthen the argument that Ardipithecus represents the best available model for what the last common ancestor of humans and chimps looked like, Simpson's group contends (SN: 1/16/10, p. 22). Some researchers regard living chimpanzees as reasonable examples of a last common ancestor. Yet Ardi and her Gona cohorts, among their many nonchimplike characteristics, display no signs of knuckle-walking or being able to swing by their arms through trees. So evolutionary predecessors of Ardi's kind were unlikely to look much like chimps, Simpson says.

DeSilva agrees, but adds that too few fossils from 5 million to 9 million years ago have been found to clarify what the last common ancestor of human and chimps actually looked like.

S. Simpson et al. Ardipithecus ramidus postcrania from the Gona Project area, Afar regional state, Ethiopia. Journal of Human Evolution. Vol. 129, April 2019, p. 1. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.12.005.

Source: https://www.sciencenews.org/article/african-hominid-ardipithecus-ramidus-fossils-upright-walking

|

![]()

|

Hundreds of Mysterious Stone Structures Discovered in Western Sahara

4 February 2019

Hundreds of stone structures dating back thousands of years have been discovered in the Western Sahara, a territory in Africa little explored by archaeologists.

The structures seem to come in all sizes and shapes, and archaeologists aren't sure what many of then were used for or when they were created, archaeologists report in the book "The Archaeology of Western Sahara: A Synthesis of Fieldwork, 2002 to 2009" (Oxbow Books, 2018).

About 75 percent of the Western Saharan territory, including most of the coastline, is controlled by Morocco, while 25 percent is controlled by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. Before 1991, the two governments were in a state of war.

Between 2002 and 2009, archaeologists worked in the field surveying the landscape and doing a small amount of excavation in the part of Western Sahara that is controlled by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. They also investigated satellite images on Google Earth, they wrote in the book.

"Due to its history of conflict, detailed archaeological and palaeoenvironmental research in Western Sahara has been extremely limited," wrote Joanne Clarke, a senior lecturer at the University of East Anglia, and Nick Brooks, an independent researcher.

"The archaeological map of Western Sahara remains literally and figuratively almost blank as far as the wider international archaeological research community is concerned, particularly away from the Atlantic coast," wrote Clarke and Brooks, noting that people living in the area know of the stone structures, and some work has been done by Spanish researchers on rock art in Western Sahara.

Mysterious structures

The stone structures are designed in a wide variety of ways. Some are shaped like crescents, others form circles, some are in straight lines, some in rectangular shapes that look like a platform; some structures consist of rocks that have been piled up into a heap. And some of the structures use a combination of these designs. For instance, one structure has a mix of straight lines, stone circles, a platform and rock piles that altogether form a complex about 2,066 feet (630 meters) long, the archaeologists noted in the book.

Though the archaeologists are unsure of the purpose of many of the structures, they said some of them may mark the location of graves. Little excavation has been done on the structures, and archaeologists have found few artifacts that can be dated using a radiocarbon method. Among the few excavated sites are two "tumuli" (heaps of rock) that contain human burials dating back around 1,500 years.

Research suggests that Western Sahara was once a wetter place that could sustain more animal life than it does today. Archaeologists documented rock art showing images of cattle, giraffe, oryx and Barbary sheep while environmental researchers found evidence for lakes and other water sources that dried up thousands of years ago.

Security problems

At present, security problems in the region mean that fieldwork has stopped, Clarke and Brooks told Live Science. The terrorist group al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb operates in the desert regions near Western Sahara, and in 2013 they kidnapped two Spanish aid workers at a refugee camp in Tindouf, Algeria, just across the border from Western Sahara.

While the Sahrawi people and Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic strongly oppose the terrorist group, it's extremely difficult for authorities to effectively patrol the vast desert areas where the stone structures are located, Clarke and Brooks said. This means archaeologists can't work there safely right now. This problem is not unique to Western Sahara, as the security risks posed by terrorist and extremist groups in the region mean that archaeologists can't work in much of North Africa right now, they said.

Source: https://www.livescience.com/64677-stone-structures-discovered-western-sahara.html

|

![]()

|

European colonizers killed so many Native Americans that it changed the global climate

2 February 2019

When Europeans arrived in the Americas, they caused so much death and disease that it changed the global climate, a new study finds.

European settlers killed 56 million indigenous people over about 100 years in South, Central and North America, causing large swaths of farmland to be abandoned and reforested, researchers at University College London, or UCL, estimate. The increase in trees and vegetation across an area the size of France resulted in a massive decrease in carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere, according to the study.

Carbon levels changed enough to cool the Earth by 1610, researchers found. Columbus arrived in 1492,

"CO2 and climate had been relatively stable until this point," said UCL Geography Professor Mark Maslin, one of the study's co-authors. "So, this is the first major change we see in the Earth's greenhouse gases."

Before this study, some scientists had argued the temperature change in the 1600s, called the Little Ice Age, was caused only by natural forces.

But by combining archaeological evidence, historical data and analysis of carbon found in Antarctic ice, the UCL researchers showed how the reforestation -- directly caused by the Europeans' arrival -- was a key component of the global chill, they said.

"For once, we've been able to balance all the boxes and realize that the only way the Little Ice Age was so intense is ... because of the genocide of millions of people," Maslin told CNN.

The methodology

Researchers analyzed Antarctic ice, which traps atmospheric gas and can reveal how much carbon dioxide was in the atmosphere centuries ago.

"The ice cores showed that there was a larger dip in CO2 (than usual) in 1610, which was caused by the land and not the oceans," said Alexander Koch, lead author of the study.

A small shift in temperatures -- about a 10th of a degree in the 17th century -- led to colder winters, frosty summers and failing harvests, Koch said.

The implications

The implications of the study go beyond climate science and also contribute to research in geography and history, Maslin said, noting that deaths of indigenous Americans directly contributed to the success of the European economy.

Natural resources and food shipped from the New World helped Europe's population to expand. It also allowed people to stop farming for sustenance and begin working in other industries for spare money.

"The really weird thing is, the depopulation of the Americas may have inadvertently allowed the Europeans to dominate the world," Maslin said. "It also allowed for the Industrial Revolution and for Europeans to continue that domination."

Source: https://edition.cnn.com/2019/02/01/world/european-colonization-climate-change-trnd/index.html

|

|

Archaeologists uncover South Africa's lost city of Kweneng

1 February 2019

Where is the lost city of Kweneng located?

The ancient city of Kweneng is believed to be a 200-year-old stretch of land that is located about 50km south of Johannesburg.

Professor Karim Sadr led a team of achaeologists to excavate the area. Even more exciting is the advanced laser technology the team used to map out satellite images of the city that once housed a colony of up to 20 000 citizens.

Featured on a BBC News report from October 2018 is a video showing how the researchers were able to recreate this moment from centuries ago. In it, Professor Sadr explained, in great detail, how the laser technology was able to create, with impressive accuracy, the ancient city.

"As soon as each pulse (sent out by the lasers) hits an object, any solid object, a bird, a leaf or a tree or the ground, it reflects that straight back into the machine. The machine can then figure out where that interception took place in three dimensions," he explained.

Professor Sadr believes that Kweneng was once home to the Setswana-speaking people. In many respects, it was a thriving city with hundreds of homesteads and trade networks.

The professor holds a strong view that the city functioned similarly to how ours do in contemporary times. It had different levels of government, a civilised burial tradition and civic duties.

"There were four or five levels of local government, probably with regiments organised by age that could be called up for civic work or war. They buried their important dead under the walls of the central cattle enclosures but there was a very strong egalitarian tradition and the king went out of his way to not stand out,"

Professor Sadr has the extinction date of the ancient city marked at around the end of the 18th century, right before the birth of the city of Johannesburg.

Based on archaeological evidence, it may be that the inhabitants of the city were affected by mass killings or some sort of mass wipe out.

"My guess is that the whole city was hit hard. The question is whether it was totally destroyed," he added.

It's an incredible feat to find a way to open up a window that could allow us to peer into our rich and complex past.

Source: https://www.thesouthafrican.com/lifestyle/archaeologists-uncover-south-africas-lost-city-kweneng/

|

Australopithecus sediba. Alexander Joe/AFP/Getty Images

|

'Missing link' in human history confirmed after long debate

20 January 2019

Early humans were still swinging from trees two million years ago, scientists have said, after confirming a set of contentious fossils represents a "missing link" in humanity's family tree.

The fossils of Australopithecus sediba have fueled scientific debate since they were found at the Malapa Fossil Site in South Africa 10 years ago.

And now researchers have established that they are closely linked to the Homo genus, representing a bridging species between early humans and their predecessors, proving that early humans were still swinging from trees 2 million years ago.

The Malapa site, South Africa's "Cradle of Humankind," was famously discovere by accident by nine-year-old Matthew Berger as he chased after his dog.

That stroke of luck eventually led to this week's finding, detailed in the journal "Paleoanthropology."d

The findings help fill a gap in humankind's history, sliding in between the famous 3-million-year-old skeleton of "Lucy" and the "handy man" Homo habilis, which was found to be using tools between 1.5 and 2.1 million years ago.

They show that early humans of the period "spent significant time climbing in trees, perhaps for foraging and protection from predators," according to the study in the journal "Paleoanthropology."

"This larger picture sheds light on the lifeways of A. sediba and also on a major transition in hominin evolution," said lead researcher Scott Williams of New York University.

Two partial australopith skeletons - a male and a female - were found in 2008 at a collapsed cave in Malapa, in South Africa's "Cradle of Humankind."

"Australopithecus" means "southern ape," a genus of hominins which lived some 2 million years ago.

Their discovery set off years of debate in the scientific community, with some rejecting the idea that they were from a previously undiscovered species with close links to the homo genus and others floating the idea that they were from two different species altogether.

But the new research has laid those suggestions to rest, and outlined "numerous features" the skeletons share with fossils from the homo genus.

Australopithecus sediba's hands and feet, for instance, show it was spending a good amount of time climbing in trees. The hands have grasping capabilities, which are more advanced than those of Homo habilis, suggesting it, too, was an early tool-user.

The researchers of the paper to highlight the remarkable story of how the fossils were found, pointing out that other dramatic clues to humanity's history are still waiting to see the light of day.

"The first fossil of A. Sediba was discovered by Matthew Berger, then a nine-year-old, who happened to stop and examine the rock he tripped over while following his dog Tau away from the Malapa pit," they wrote.

"Imagine for a moment that Matthew stumbled over the rock and continued following his dog without noticing the fossil," they added.

"If those events had occurred instead, our science would not know about A. sediba, but those fossils would still be there, still encased in calcified clastic sediments, still waiting to be discovered."

"The fortuitous discovery of the Malapa fossils and other similarly fortuitous recent finds should be reminders to us all that there is still so much to discover about our evolutionary past," the authors concluded.

Source: https://edition.cnn.com/2019/01/19/health/australopithecus-sediba-human-history-scli-intl/index.html

|